SHORTY LOVELACE HISTORIC DISTRICT

|

|

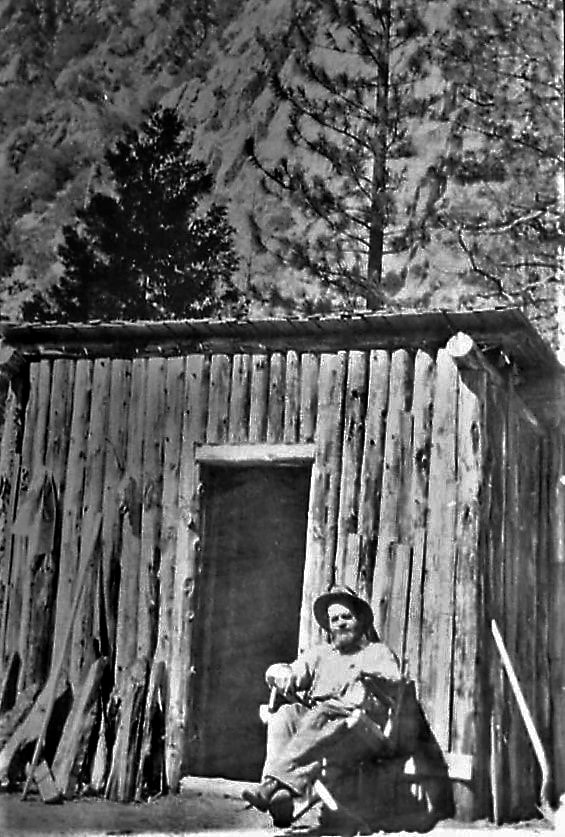

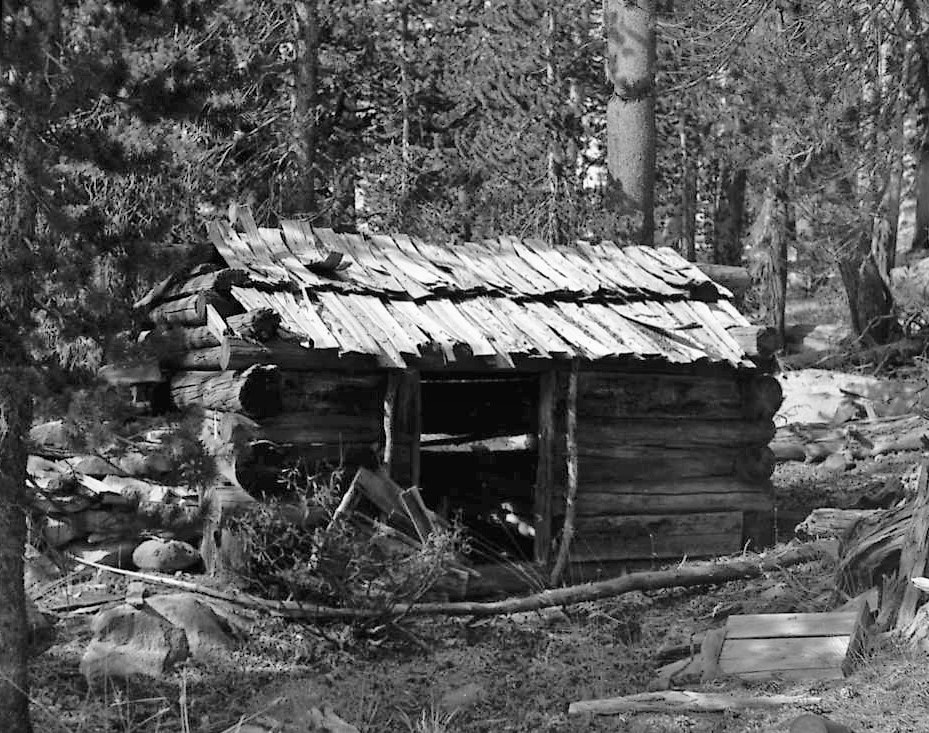

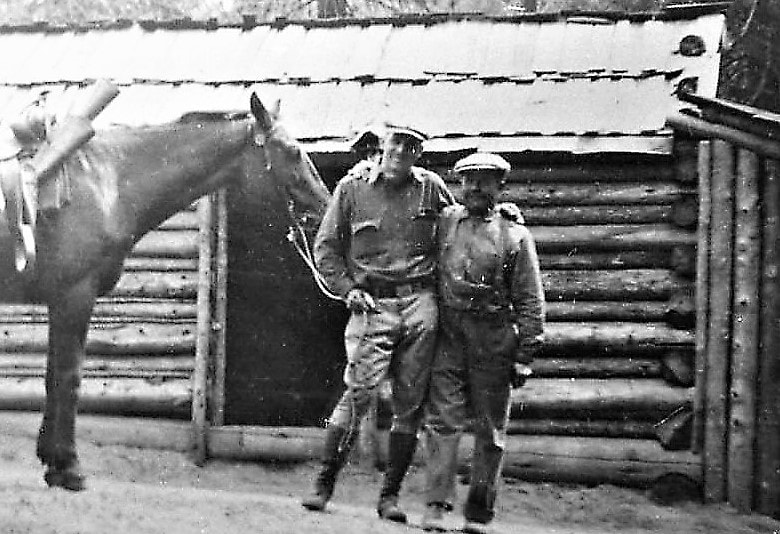

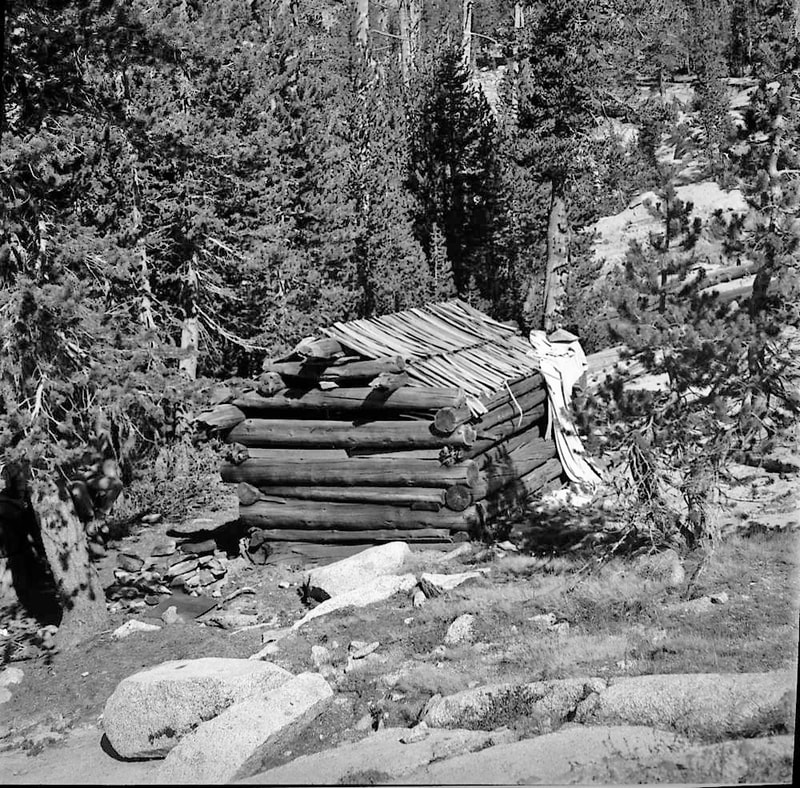

Recognizing Tulare County's Last True Mountain Man by Laurie Schwaller Joseph Walter "Shorty" Lovelace may not have looked like the classic image of a mountain man, but the National Historic District bearing his name in the rugged high Sierra Nevada of Kings Canyon National Park is a testament to the lifeway, ingenuity, and endurance Shorty embodied for forty years as a totally self-sufficient fur-trapping mountain man. |

Maps, Directions, and Site Details:

|

|

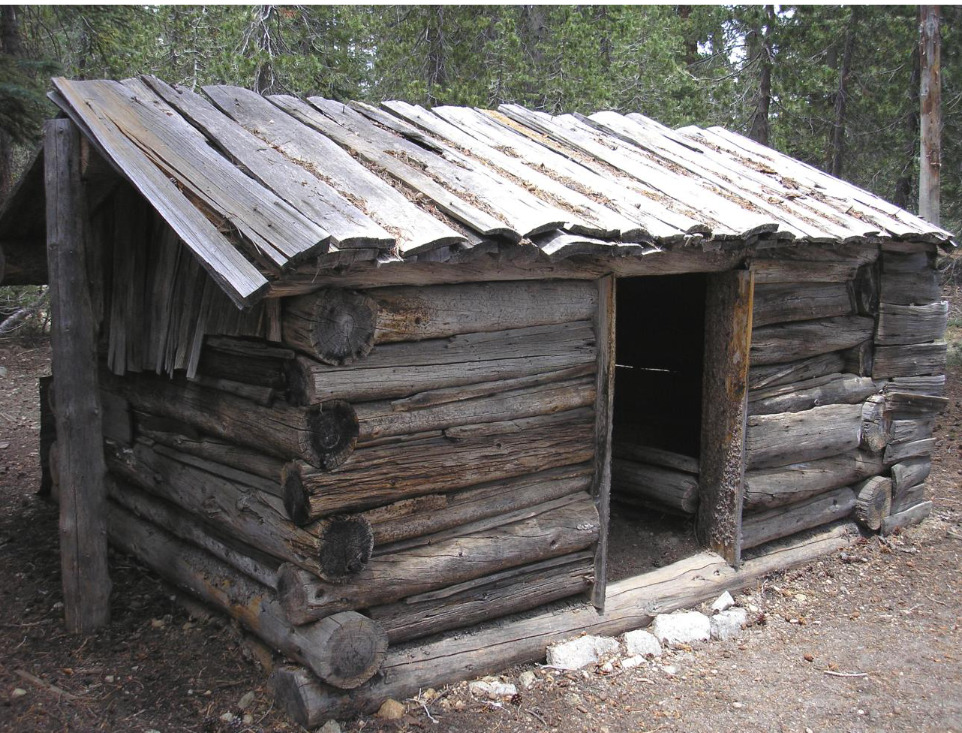

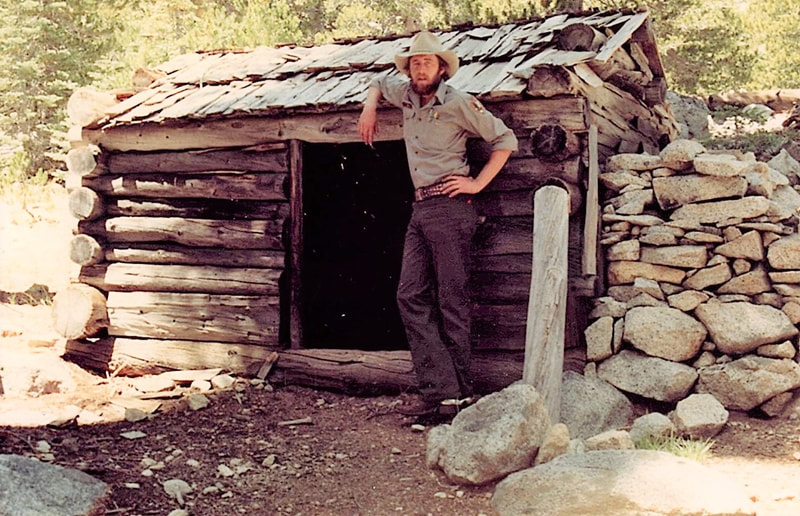

The Historic District comprises nine sites in Kings Canyon N.P. where remains of Shorty's shelters could still be seen in 1978 when the District was listed on the NRHP. The sites are accessible only by foot/stock trail. Wilderness Permits are required for all overnight trips.

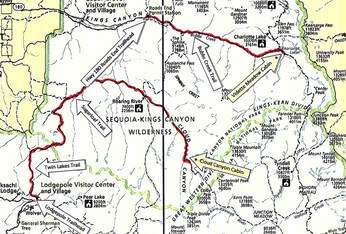

By 1978, only the cabins at Vidette Meadow and Cloud Canyon were sufficiently intact to allow for structural preservation. The other sites are near Woods Creek Crossing, Granite Pass, Gardiner Basin, Bubbs Creek, Sphinx Creek, Crowley Canyon, and Williams Meadow. "[S]ufficient . . . sites remain to document in rare detail the operative patterns of an alpine fur trapping circuit. . . . {T]his [may be] the only such opportunity present within the national park system." -- NRHP Nomination Form The most-visited of Shorty's cabins in Kings Canyon N.P. is near Vidette Meadow, just north of the Tulare County line. It can be reached via the Bubbs Creek Trail out of Hwy 180 Road's End, a few miles east of Cedar Grove in the bottom of Kings Canyon. At the junction of the Bubbs Creek Trail with the John Muir Trail, go south a short distance on the John Muir to the area of the bear box campsite and the junction with the Vidette Lakes Trail. This cabin can also be reached via the Onion Valley Trailhead off Hwy 395 on the east side of the Sierra. Shorty's cabin in Cloud Canyon can be reached from Lodgepole in Sequoia N.P. via the Twin Lakes Trail, which quickly enters Kings Canyon N.P., then via the Sugarloaf Trail to the locale of the Roaring River Ranger Station and up Cloud Canyon on the Colby Pass Trail about 6 miles to the area of the cabin. This cabin can also be reached from the Rowell Meadow trailhead in Giant Sequoia National Monument. Follow this trail to Comanche Meadow and then take the Sugarloaf Trail to the Roaring River Ranger Station and up Cloud Canyon on the Colby Pass Trail to the area of the cabin.

|

Environment: Mountains, meadows, elevation varies, Kings Canyon National Park

Activities: architecture study, backpacking, birding, camping (near several of the sites), fishing (license required), hiking, history, photography, wildlife viewing (NOTE: the structures, ruins, and sites of Shorty's shelters can be visited only by foot or stock trail.)

Open: Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks are always open, weather permitting, unless closed due to emergency conditions; park entrance fee; Wilderness Permit required for all overnight trips

Site Steward: National Park Service-Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks; 559-565-3341; www.nps.gov/seki

Opportunities for Involvement: Sequoia Parks Conservancy (SPC) membership, donate, volunteer

Links: National Register of Historic Places documentation, https://www.nps.gov/seki/planyourvisit/wilderness_permits.htm

Books: 1) Shorty Lovelace, Kings Canyon Fur Trapper, by William Tweed (Sequoia Natural History Association, 1980, 2007)

2) A Branch of the Sky, Fifty Years of Adventure, Tragedy, & Restoration in the Sierra Nevada, by Steve Sorensen (Picacho, 2018)

Photos for this article courtesy of: Victor Blakey/Victor Blakey Fine Art; City of San Gabriel, CA; climber.org/reports/2013/1844;

Tim Gage, Vancouver, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0; Sandra Harris/ShortyLovelace.com; Cory Hayes; Moose Henderson; Ben Hogan/manystepsmakemountains.com; Zachary Just; Kathleen McCleary; National Park Service; Leor Pantilat; Don Paulson; Gianna [email protected]; Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Archives (including photos by J.E. Armstrong, Richard McLaren, Don Sides, Scottie Steenburgh, and Lowell Sumner); Chad Thomas; Tulare County Library, Sesquicentennial Collection; Thor Riksheim/NPS; USDA Forest Service, Sierra National Forest Heritage Places; and wenthiking.com, photo by Stacey went backpacking

Tim Gage, Vancouver, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0; Sandra Harris/ShortyLovelace.com; Cory Hayes; Moose Henderson; Ben Hogan/manystepsmakemountains.com; Zachary Just; Kathleen McCleary; National Park Service; Leor Pantilat; Don Paulson; Gianna [email protected]; Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Archives (including photos by J.E. Armstrong, Richard McLaren, Don Sides, Scottie Steenburgh, and Lowell Sumner); Chad Thomas; Tulare County Library, Sesquicentennial Collection; Thor Riksheim/NPS; USDA Forest Service, Sierra National Forest Heritage Places; and wenthiking.com, photo by Stacey went backpacking