Click on Map to Enlarge Click on Map to Enlarge

"If the meadows of Giant Forest are special places, there can be little doubt that Crescent and Log meadows, each more than half a mile long, are the most special of all. A walk around the two meadows offers wonderful views of the giant sequoias, a visit to the oldest pioneer cabin in Sequoia National Park, and, in season, vistas of flower-filled meadows." -- William Tweed, 1987

|

THARP'S LOG Environment: Mountains, subalpine meadows, giant sequoia forest, elevation: about 6800'; Sequoia National Park (NOTE: Tharp's Log is accessible only by foot trail; no dogs on park trails.) Activities: study of architecture and landscape architecture, birding, camping (nearby, at Lodgepole, seasonal), hiking, history, photography, picnicking (at Crescent Meadow), wildlife viewing Open: Sequoia National Park is always open, weather permitting (unless closed due to emergency conditions); park entrance fee Site Steward: National Park Service-Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks; 559-565-3341; www.nps.gov/seki Opportunities for Involvement: donate, volunteer Links: National Register of Historic Places documentation; Sequoia Kings Canyon - Plan Your Visit; Tulare County Treasures - Giant Forest (includes video) Books: Challenge of the Big Trees -The History of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks, revised edition by William C. Tweed and Lary M. Dilsaver, George F. Thompson Publishing, 2016 Directions: Map and directions are at the bottom of this page. |

"The scout for the wagon train was a rather brash, but well qualified young man who went by the name Hale Tharp. That he was also a keen shot proved handy for providing meat for the frying pan and protection from wild animal or Indian attack." -- Dallas Pattee, 1999, great great great niece of Chloe Ann Smith Swanson Tharp

"There were about 2,000 Indians then living along the Kaweah River above where Lemon Cove now stands. . . . . But few of them had ever seen a white man prior to my arrival. The Indians all liked me because I was good to them. I shot many deer for them to eat, as they had no firearms and knew nothing about firearms. I liked the Indians, too for they were honest and kind to each other. I never knew of a theft or murder amongst them." -- Hale Tharp in 1910 interview by Sequoia N.P. Chief Ranger Walter Fry

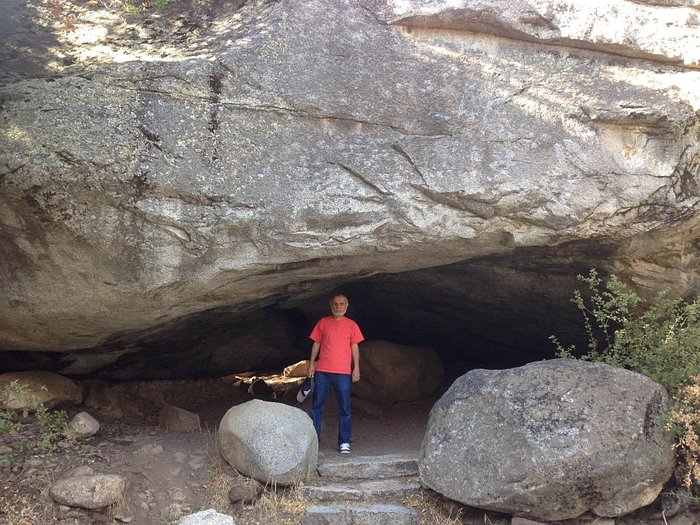

"In his account of visiting Chief Chappo's village at Hospital Rock, [Tharp] speaks with admiration and respect for the cleanliness and thrift of the Indians he found there and he considered Chappo, or Ho-Nush, as the Indians called him, a good friend. . . . [The Indians] told him about the big trees which 25 men with hands clasped could circle." -- Los Tulares #39, 1959

Hospital Rock Pictographs Hospital Rock Pictographs

"Tharp recalls . . . [T]he Indians . . . had contracted contagious diseases from the whites, such as measles, scarlet fever and smallpox, and they died off by the hundreds. I helped to bury 27 in one day up on the Sam Kelly place.'" -- Mike Whitney, 2017

"During the early 1860s, after a rapid buildup of interior grazing activity, two successive events, the great Central Valley flood of 1862 and the severe drought of 1863-1864, shook the grazing industry to its foundations. The drought especially, with its near total failure of winter-pasture grasses, sent stockmen desperately searching for previously unused rangelands. What resulted was the first utilization of the Sierra for large-scale livestock feeding." -- William C. Tweed and Lary M. Dilsaver, 2016

"By the summer of 1864, as many as 4,000 cattle were in the Giant Forest areas. . . . Within a few years, much of the herbaceous vegetation of the Sierra was either destroyed or replaced." -- William C. Tweed and Lary M. Dilsaver, 2016

"The effective replacement of the Native American population of the southern Sierra with a population of Caucasian settlers had a profound effect upon the land. Both cultures looked to the land for sustenance, but in very different ways. . . . The new people saw nature not as a part of the same psychological world as that of humanity but as something provided by God for their consumption and use." -- William C. Tweed and Lary M. Dilsaver, 2016

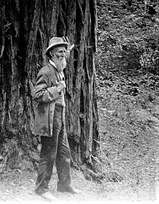

Muir by Giant Sequoia Muir by Giant Sequoia

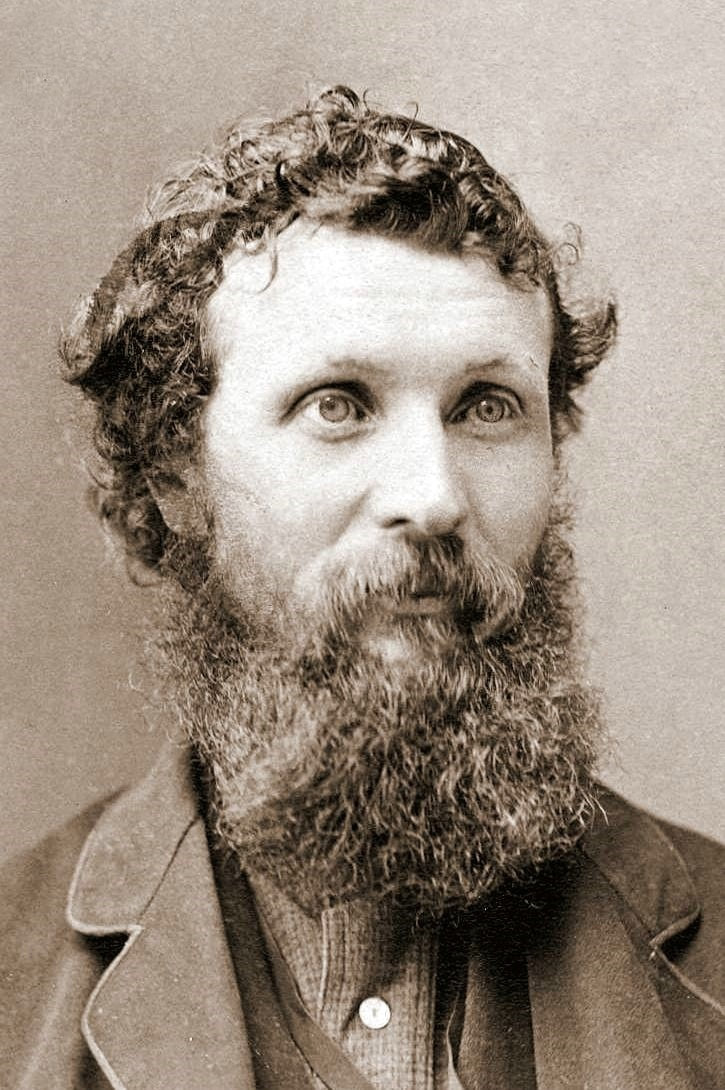

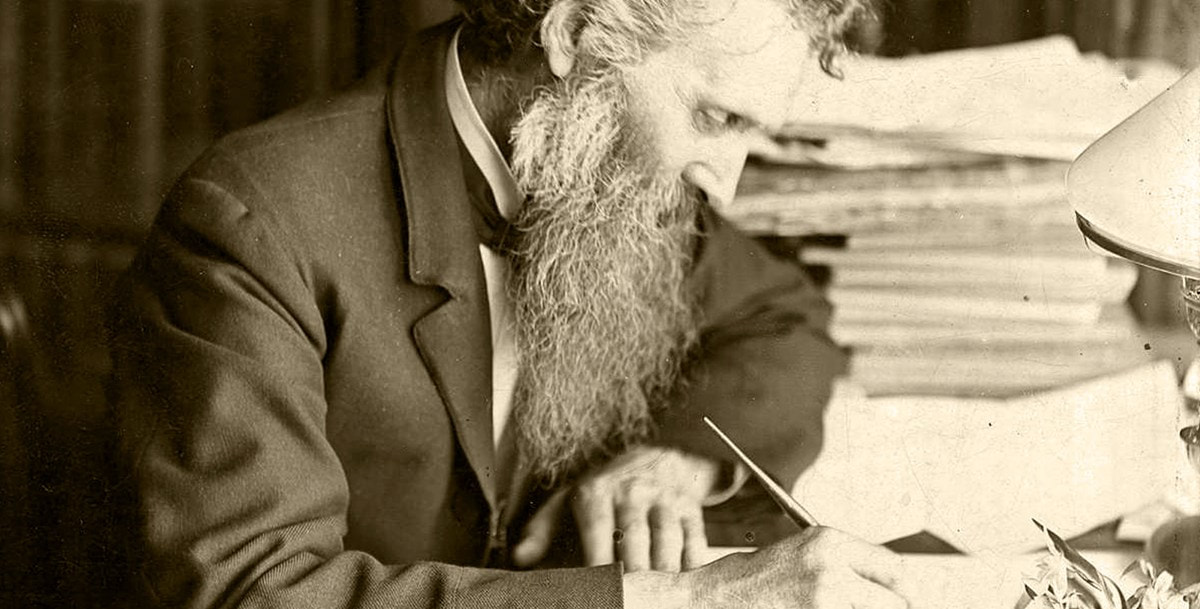

"[A] man and horse came in sight at the farther end of the meadow .. . . I explained that I came across the canyons from Yosemite and was only looking at the trees. 'Oh then, I know,' he said, greatly to my surprise, 'you must be John Muir. . . . Just take my track and it will lead you to my camp . . . . [M]ake yourself at home.'" -- John Muir, 1901

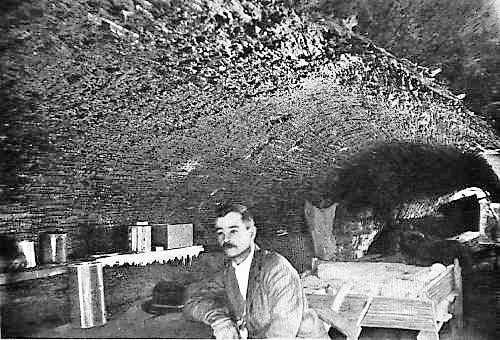

"[I[ discovered his noble den in a fallen Sequoia hollowed by fire -- a spacious loghouse of one log, carbon-lined, centuries old yet sweet and fresh, weather proof, earthquake proof, likely to outlast the most durable stone castle, and commanding views of garden and grove grander far than the richest king ever enjoyed." -- John Muir, 1901

"[U]p spring the mighty walls of verdure three hundred feet high, the brown fluted pillars so thick and tall and strong they seem fit to uphold the sky . . . ." -- John Muir, 1901  John Muir, 1872 John Muir, 1872

"Soon the good Samaritan mountaineer came in, and I enjoyed a famous rest listening to his observations on trees, animals, adventures, etc., while he was busily preparing supper." -- John Muir, 1901  Chief Ranger Walter Fry Chief Ranger Walter Fry

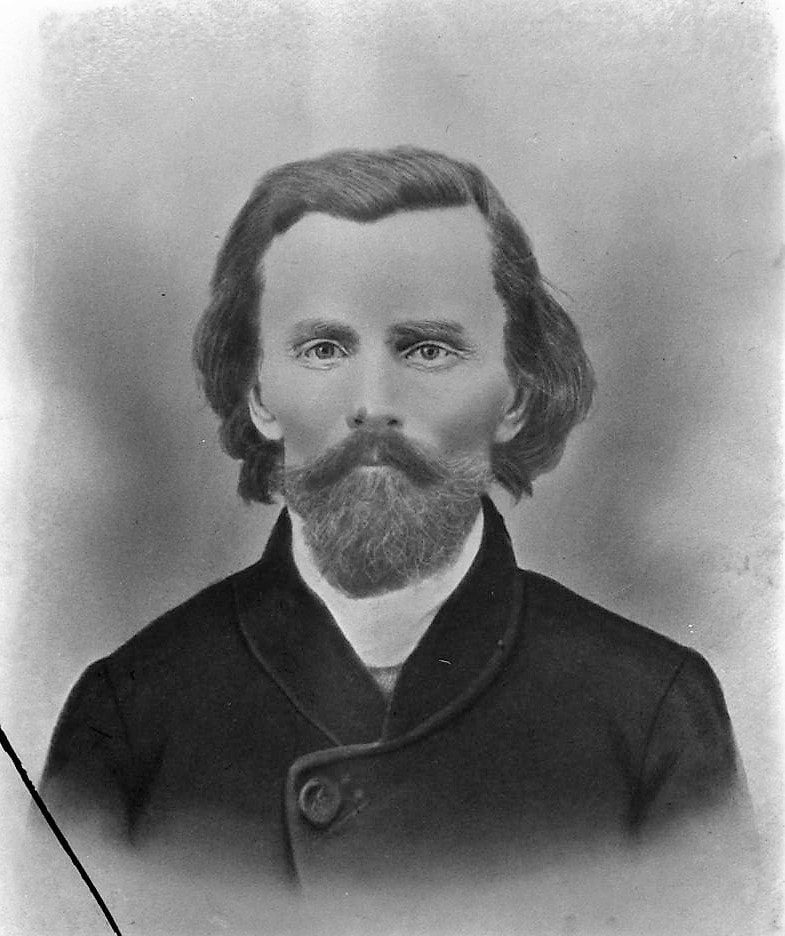

In May, 1910, Sequoia National Park Chief Ranger Walter Fry interviewed Hale Tharp as the first white man to discover and explore the Three Rivers and park country. This interview is the basis of most of what we know of Tharp's story.

Looking West: Log Mdw., Moro Rock, Middle Fork of Kaweah River Looking West: Log Mdw., Moro Rock, Middle Fork of Kaweah River

[Tharp] told Fry, that "[U]p to 1890, when the park was created, I held the Giant Forest country as my range and some of my family went there every year with stock. When the land up there was thrown on the market, with other men we bought large holdings some of which Nort, my son, still owns."

In 1912, at age 82, Tharp died at his ranch home near Three Rivers. He was buried beside his wife at Hamilton Cemetery between Exeter and Woodlake. His gravestone names him "Discoverer of the Giant Forest."

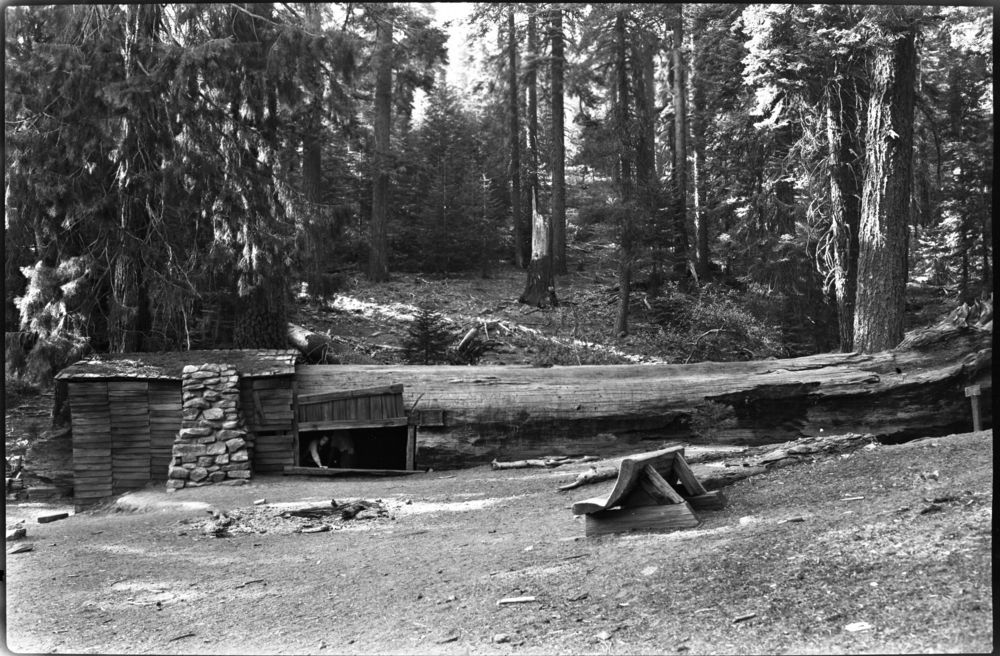

Three Rivers Woman's Club at Tharp's Log, 1923 Three Rivers Woman's Club at Tharp's Log, 1923

"To earn money for our various charities, we ladies of the Three Rivers Woman’s Club held old-time dances and card parties, served meals to many local and out-of-town organizations, held apple festivals and bazaars, presented plays, sold magazine subscriptions, and baked pies to sell. . . . Money was donated for gates to the Three Rivers Cemetery, and for the restoration of Tharp’s Log in Sequoia National Park." -- Wilma Kauling, 2016

Photos for this article by: John Greening, Gary Kunkel, and Laurie Schwaller; and courtesy of David Baselt; Steven Campbell/Find A Grave; Ghaith391/Tripadvisor; Golden Gate National Recreation Area Archives; National Park Service; Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Archives; Sierra Club John Muir Exhibit/Sierra Club Vault; Traditions of the Ancestors, public domain; Tulare County Library, Annie R. Mitchell History Room; Tulare County Office of Education, F. Lata and A. Barr, Kern River Historical Reenactment; University of California, Davis, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, photo by Chris Nicolini; and University of the Pacific, Holt-Atherton Library

|

History:

Tharp's Log -- The One-Log Cabin of the "Discoverer" of the Giant Forest by Laurie Schwaller The gentle loop trail from the foot of Crescent Meadow to Tharp's Log is one of the easiest and loveliest in Sequoia National Park. In just under a mile, at the top of this loop, lies the oldest man-made structure in the Park. It is a truly unique tree house -- a genuine log cabin. Hale Dixon Tharp, the pioneer rancher who is credited with being the first Caucasian American to discover and explore the Giant Forest, modified this fire-hollowed fallen sequoia tree in 1861 to provide a comfortable, convenient, weather-proof dwelling for his summer sojourns there. Ten years earlier, the Michigan-born 23-year-old Tharp had come to California with a wagon train. He had been hired by Mrs. Chloe Ann Smith Swanson, an Illinois widow with four young sons, to drive her prairie schooner across the country to Placerville. There, Tharp began working in the gold mines, and soon married Mrs. Swanson. But after a mining injury, he decided to find a better way to make a living. Reasoning that California's growing population would continue to make a ready market for beef, he went searching for free range for cattle.

It was 1856, one of California's worst drought years, but eventually, Tharp found what he what he was looking for. In Tulare County, he followed the Kaweah River east from Visalia. Where the Kaweah ran through a broad plain bordered by the last high foothills (now the site of Lake Kaweah), water, grass, and game abounded, and the hundreds of Native Americans living in the area seemed friendly and curious about the first Euro-American most of them had ever seen. Near the confluence of Horse Creek and the Kaweah (about 2-1/2 miles below what is now the town of Three Rivers), Tharp made a preemption claim on the land, erected a brush shelter as an improvement, and returned to Placerville. Two years later, he came back to his Kaweah homestead with his brother-in-law, John Swanson. They built a cabin and a barn, then explored the area further, looking for summer pasturage for their cattle. Tharp befriended his Native American neighbors, visited their large village at Hospital Rock, and was intrigued by their stories of green meadows and gigantic trees in the nearby mountains.

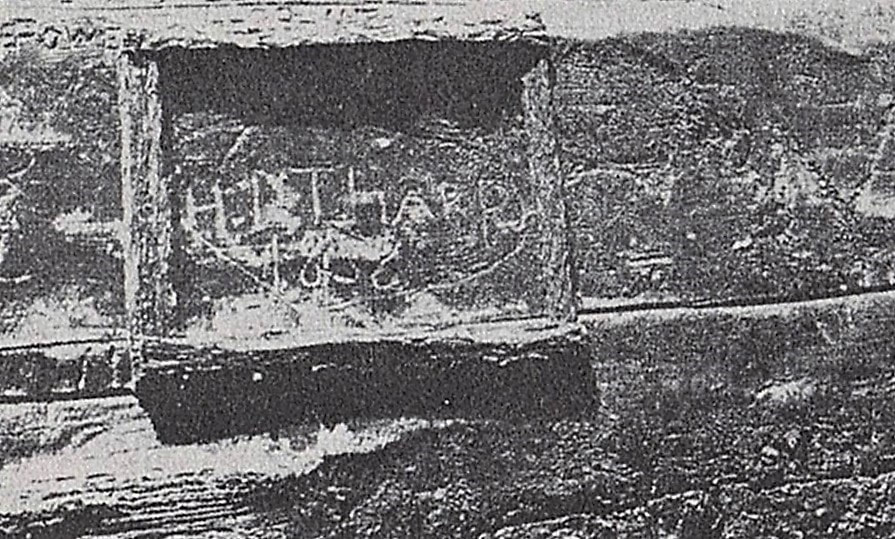

That summer, two of the local Yokuts guided him up past Moro Rock into the Giant Forest. At Crescent and Log meadows, Tharp saw excellent forage for his animals. He laid claim to the land, inscribing his name and the date, 1858, with his knife on a huge, hollow fallen sequoia at the north end of Log Meadow. Thus Tharp was not only the first Euro-American settler on the Kaweah above the Central Valley, he was also one of the first non-Indians to see this majestic sequoia forest. Soon, however, others began to settle in the Horse Creek and Three Rivers area. As a result, the local Indians were decimated by the whites' contagious diseases and steadily displaced from their homeland. By the summer of 1865, almost all were gone. Meanwhile, Tharp had moved his wife and family to Tulare County and continued to explore the mountains. By 1861, he decided that he had to take further action to hold his claim to the Giant Forest country: He drove a herd of horses up to graze Log Meadow all summer, and he turned its fallen sequoia into a summer home.

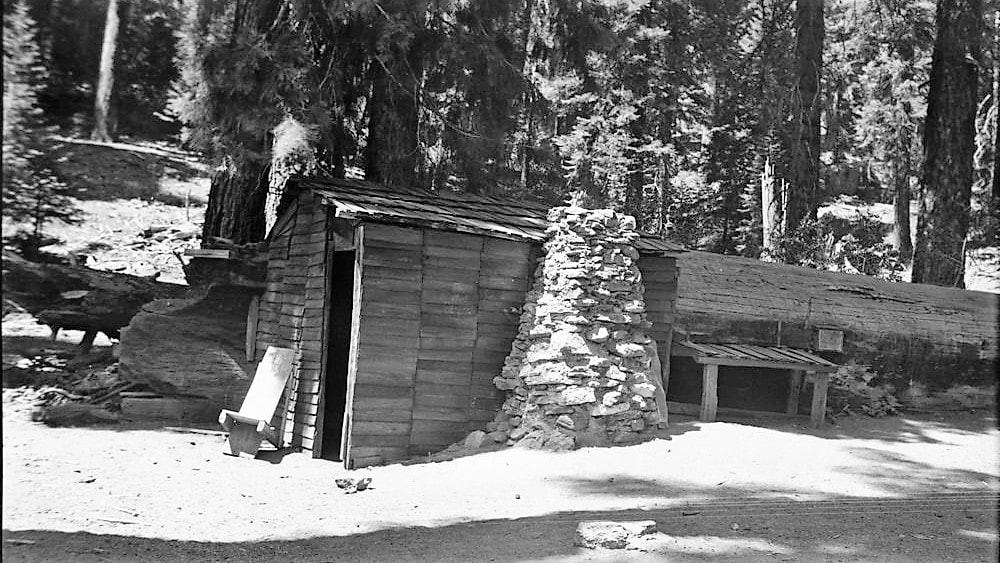

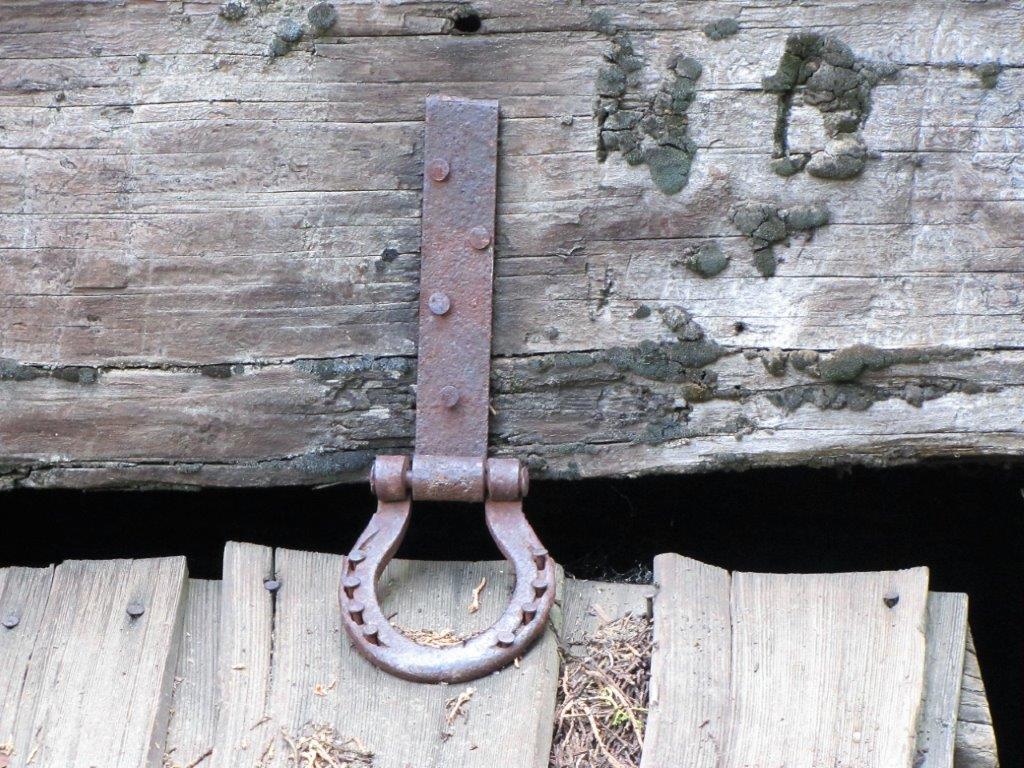

The great tree's trunk had split crosswise into two sections when it crashed to the earth some centuries before. The upper segment was not hollow, but the larger, 70-foot-long lower section was entirely hollow, its interior charcoal black from fire. Almost 55 feet of it was large enough in diameter for Tharp's use, with an interior diameter of almost six feet at the large open end. For light and ventilation, he cut a large window into the south side of the log. He made a shutter for it of redwood shakes attached to a redwood frame with hinges made from leather straps and horseshoes. He enclosed the big west end of the log with an 8 x 10 foot shake structure of three walls, a roof, and a door, but left the east end open for additional ventilation. On the cabin's south wall, he built a mud-mortared fireplace and chimney from local granite boulders. He furnished the cabin with a rough bed, table, and bench, made from massive slabs of redwood, all standing on a smooth floor of packed earth. Every year thereafter, until Sequoia National Park was created in 1890, members of Tharp's family and herds of Tharp's livestock spent summers ranging in the Giant Forest. Tharp's Log also sheltered hired hands who tended his cattle, and various visitors -- including a very famous one. Not everyone who came to the region wanted to exploit its resources for profit. In 1875, John Muir arrived, wandering over the plateau with his mule, Brownie, and marveling at the number, size, beauty, and extent of its Big Trees. Inspired, he gave it the name still used today -- Giant Forest.

Muir writes that he encountered a man on horseback, but doesn't name him. It was likely Hale Tharp or one of his sons who then invited Muir to make himself at home in his "camp in a big hollow log on the side of a meadow." Enchanted by this "noble den," and greatly enjoying his host's company and conversation, Muir spent several nights in Tharp's Log before continuing south in search of the farthest sequoias. For years thereafter, he worked and wrote tirelessly to save the Big Trees from destruction. In 1920, eight years after Tharp died, the Park Service bought the last of his inholdings in the Giant Forest, paying his son Nort $33,130 for the 120-acre tract that included Tharp's Log. Soon, the Log, also called Tharp's Cabin, was opened for public display. The Park Service restored the structure to its original condition in 1923, aided by donations from the Three Rivers Woman's Club. More work was done in the 1930s and '50s. Unfortunately, Tharp's engraving, "H.D. Tharp 1858," was destroyed by vandals in 1953, even though it had been protected for many years beneath a glass plate.

In recognition of its local significance in the field of exploration and settlement, Tharp's Log was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. The cabin is over 150 years old now; the log itself may last another thousand years. That adds a long perspective to the enjoyment of this special summer home and the contemplation of Tulare County's history. June, 2020

|

|

|

Directions: Tharp's Log is accessible only by foot trail; the primary trailhead is accessed from the Crescent Meadow parking lot. From Visalia, take Hwy 198 east to Three Rivers. Continue through Three Rivers to the park entrance station, where the road becomes the Generals Highway. This is a steep, narrow, winding road; vehicles longer than 22 feet are NOT advised from between the upcoming Potwisha Campground and the Giant Forest Museum. Follow the Generals Highway to just before the Museum, where you will turn right onto the Moro Rock/Crescent Meadow Road. Proceed to where the road dead ends at the Crescent Meadow parking area. |