GENERALS HIGHWAY STONE BRIDGES

|

|

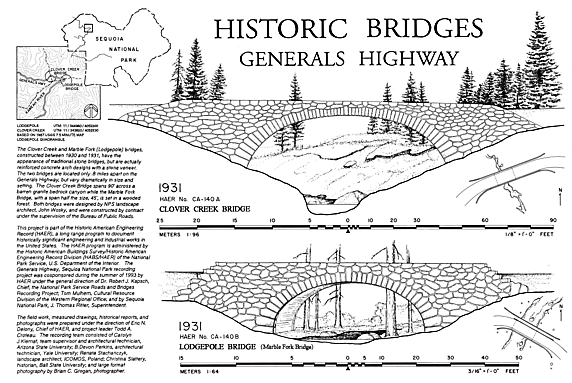

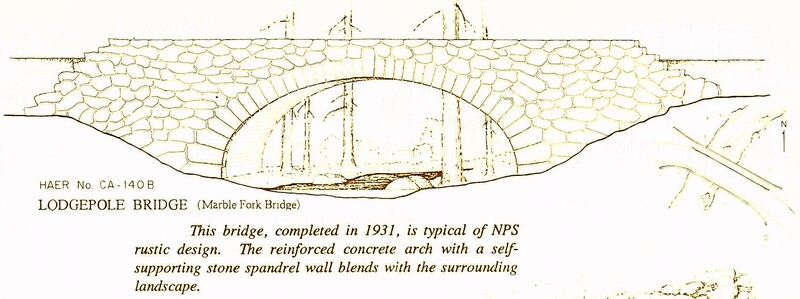

Treasures Beneath Your Wheels by Laurie Schwaller Two beautiful bridges anchor the Generals Highway Stone Bridges Historic District in Sequoia National Park. Standing about a mile apart, the Marble Fork (Lodgepole) and the Clover Creek bridges are fine examples of the National Parks' famous "rustic architecture" (or "Parkitecture"), which aims always "In the construction of roads, trails, buildings, and other improvements . . . to the harmonizing of these improvements with the landscape." In their functionality, character, and quality, these bridges fulfill the Park Service's dual mission of providing access for the enjoyment and protection of the parks' resources while leaving the parks' scenery unimpaired.

|

Colony Mill Road Cedar Creek Checking Station, 1922 Colony Mill Road Cedar Creek Checking Station, 1922

"The 1920s ushered in a new era filled with greater opportunities and a desire for travel through the introduction of the automobile. . . . . [National Park Service] Administrators were exceedingly excited about the possible benefits of a connecting road between Sequoia National Park and General Grant National Park, which became Kings Canyon National Park in 1940." -- National Park Service "When Two Parks Meet: The History of the Generals Highway"

Superintendent White Superintendent White

"The linking of the two 'general' trees gave the highway its official name, the Generals highway. The name was recommended by Sequoia National Park Superintendent John R. White and approved by Assistant National Park Service Director Horace M. Albright on 23 July 1923. The engineers building the road had at first called it 'Halawanchi,' a Monache expression for anything foolish, referring to the twisting, climbing nature of the road." -- Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service

Generals Hwy, from Amphitheater Point, 1933. Generals Hwy, from Amphitheater Point, 1933.

"National Park roadways . . . are planned for leisurely sightseeing with extreme care. They are often narrow, winding, and hilly -- but therein may lie their appeal." -- National Park Service Park Road Standards, 1984

Merel Sager, SEKI Landscape Architect Merel Sager, SEKI Landscape Architect

"A distinctive feature of park roads from the 1920s to the present is how their design and construction has been deeply influenced by landscape architects. . . . When the Bureau of Public Roads, in agreement with the National Park Service, took over control of the construction of park roads in 1926, Park Service landscape architects retained final approval for all . . . work." -- Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service

Generals Highway Road Surveyor Generals Highway Road Surveyor

"[T]he visitor often does not realize the amount of planning required during road design to produce the road that seems now to integrate so effortlessly into its surrounding landscape." -- Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service

"Numerous culverts were required along the entire length of the highway to convey mountain waters beneath the road. The majority of the culverts visible from the roadway were faced with masonry, blending with and adding to the rustic appearance of the highway." -- Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service

Quarried Stone Rock Pile Quarried Stone Rock Pile

"Stone, the landscape architects of the Park Service believed, was a material that offered high potential for non-intrusive structural design." -- William C. Tweed, NRHP Nomination Form

"Wosky Brown" Giant Forest Museum "Wosky Brown" Giant Forest Museum

John B. Wosky, the designer of the Marble Fork and Clover Creek bridges, also designed NPS buildings for decades and played a role in developing the Park Service's signature rustic architecture. "That style included a specific color of exterior paint, referred to as 'Wosky Brown,' on every building." -- University of Oregon School of Architecture and Environment and NRHP Nomination Form

Marble Fork Bridge, 1931, Measuring Rock Marble Fork Bridge, 1931, Measuring Rock

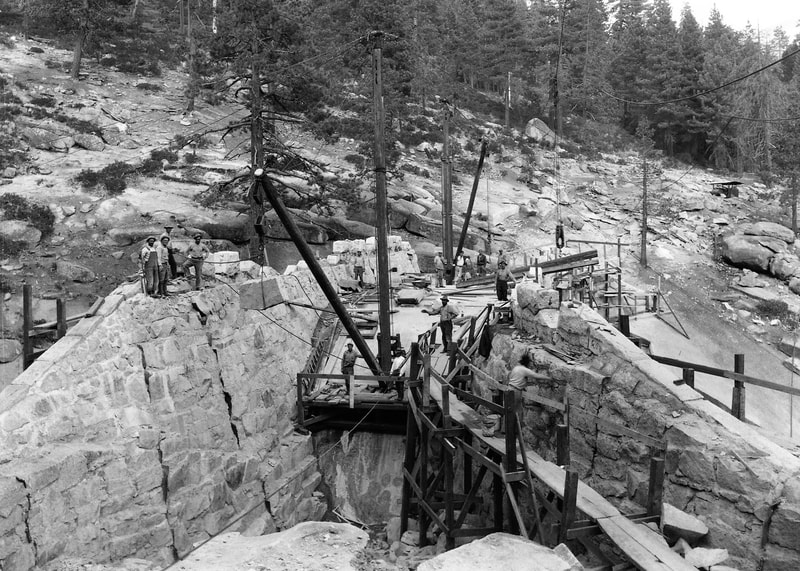

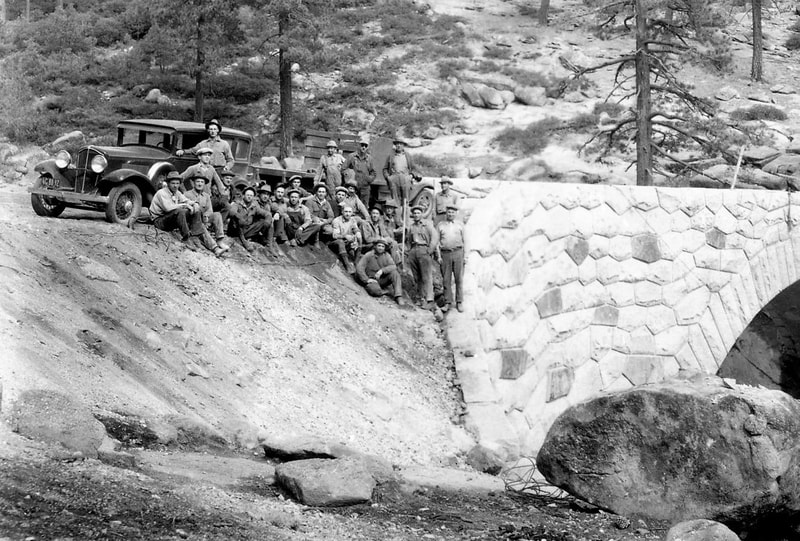

"Bids for the construction of the two bridges and the nearby Silliman Creek culvert were received on July 15, 1930, and the contract was awarded to the W. A. Bechtel Company [which] subcontracted . . . work to C.D. DeVelbiss of San Francisco. DeVelbiss hired Finnish stone cutters from a quarry at Porterville, California. Each exterior stone had to be cut to precise measurements set forth in the architectural plan." -- William C. Tweed, NRHP Nomination Form

Clover Creek Bridge Under Construction Clover Creek Bridge Under Construction

"Arches and supports of carefully cut and molded stone pleased the eye and suggested coordination with the rocky streambeds and towering cliffs nearby. They also called for backbreaking and expensive labor. Bechtel and the other companies suffered from drastic employee turnover that slowed the job . . . and exacerbated the cost overrun." -- William C. Tweed and Lary M. Dilsaver

Generals Highway Dedication Generals Highway Dedication

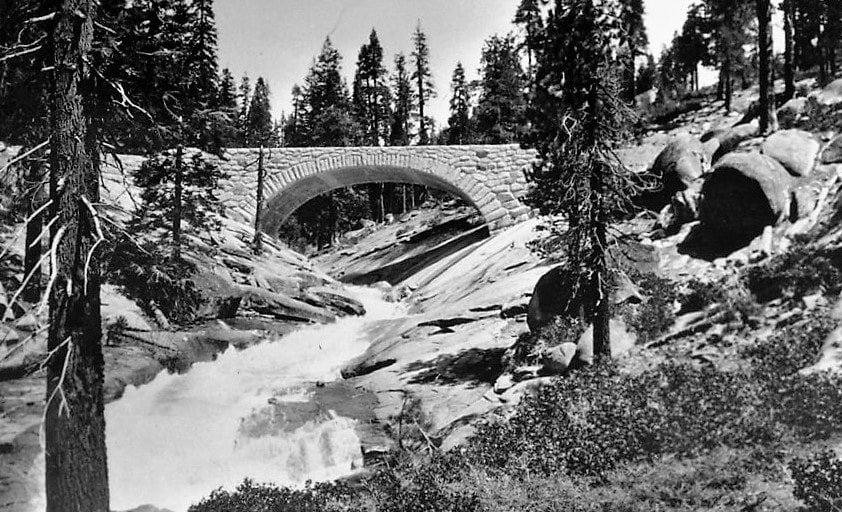

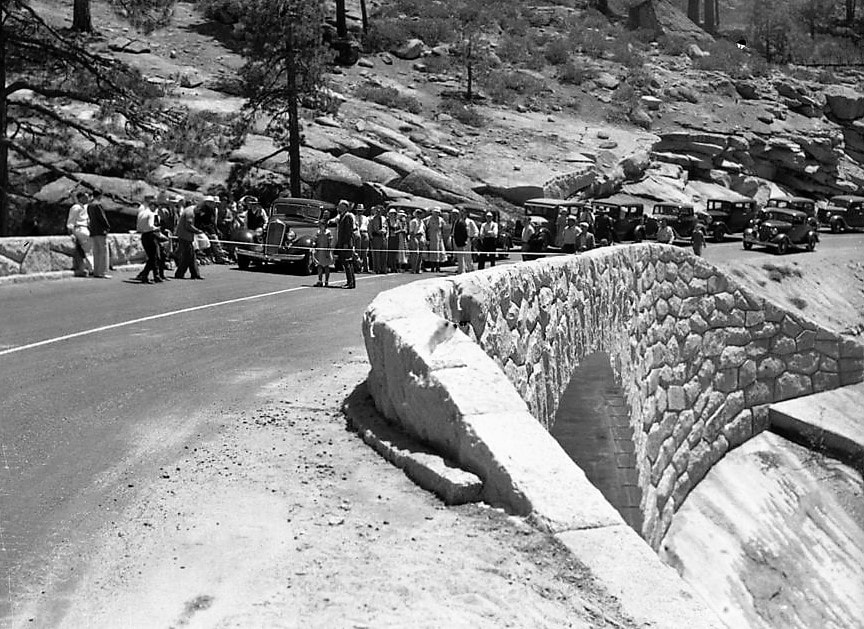

"Eagerly awaited by officials and public alike, the occasion will be an outstanding history-making episode as it will mark the attainment of a long sought goal by park officials -- that of connecting the two Big Tree Parks with an easy grade, modern mountain highway; and at a cost of 2 1/4 million dollars [a] tour of outstanding scenic splendor has been provided through both National Parks." -- National Park Service, for the Generals Highway dedication ceremonies at Clover Creek Bridge on June 23, 1935

Marble Fork Bridge Marble Fork Bridge

"The bridges were and are monuments to the engineers and landscape architects who designed them and the craftsmen and laborers who built them. They are among the last manifestations of the age of large, hand-crafted highway structures." -- William C. Tweed, NRHP Nomination Form

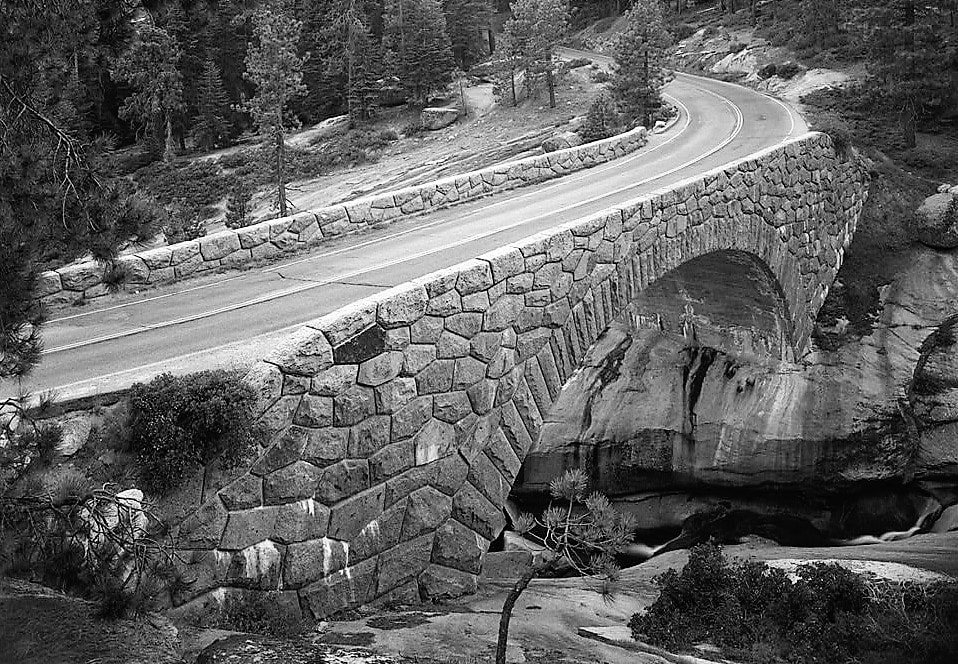

Clover Creek Bridge Clover Creek Bridge

"Dollars invested by taxpayers in the 1920s are still paying nice dividends today. Those two arches [the Marble Fork and Clover Creek bridges] ought to be as durable as anything the Romans built. I don't think there's much manmade in the park that will be there a thousand years hence, but I'd bet on the Clover Creek bridge." -- William C. Tweed, 2021

|

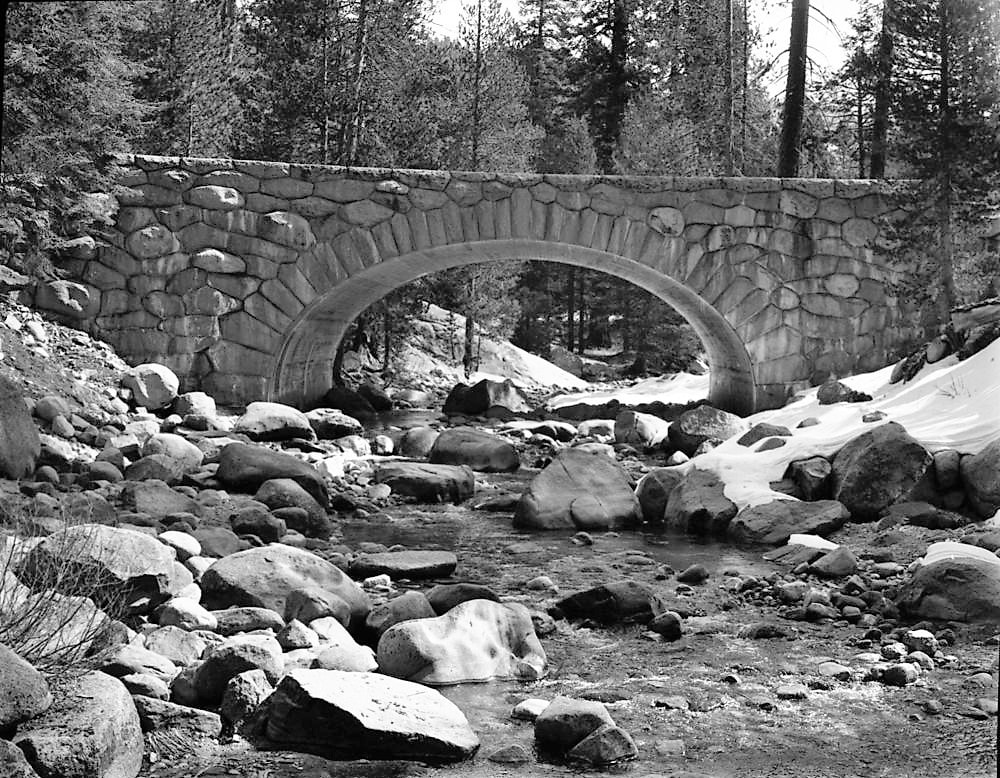

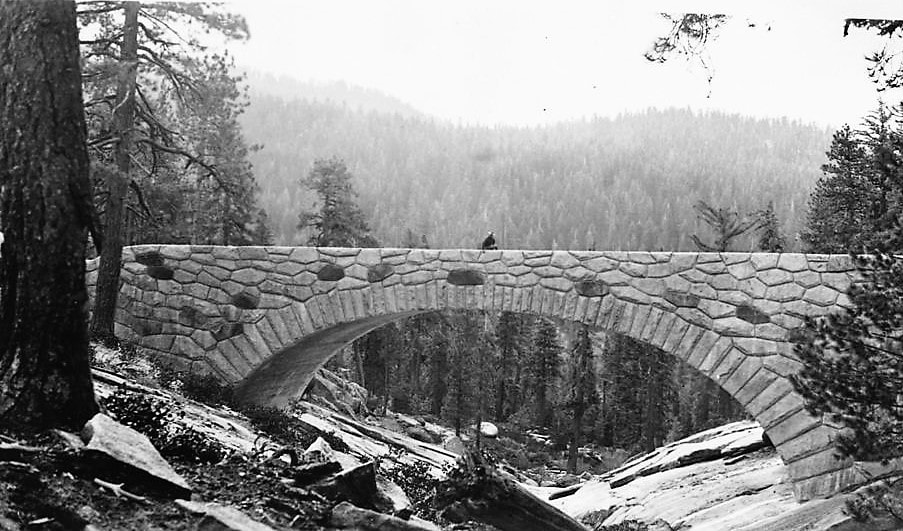

Constructed in 1930-31 as part of a 15-year project to link Sequoia and General Grant (now Kings Canyon) national parks by road, the bridges cross the Marble Fork of the Kaweah River and nearby Clover Creek. They were designed to fit "naturally" into their scenic landscapes, to endure, and to be easy to maintain.

Both are sturdy concrete and stone arch bridges. Although produced during the major economic and social crisis of the Great Depression's early years, they are models of timeless design and the work of highly skilled craftsmen, made to last. The first step in their construction was to build a concrete barrel vault one or two feet thick to span each waterway. Next, walls were added on both sides of the barrel vault and along its top.

Then the concrete walls were covered ("faced") with native stone. Instead of being cut to regular geometric shapes and laid in careful, even rows, the walls' masonry was "uncoursed" so that the stones have a natural, "rustic," unworked appearance and look almost as if they have just been stacked upon each other by some natural process. The uncoursed masonry overlays the modern construction methods and materials (e.g., rebar and concrete), creating the appearance of true stone arches. Finally, the space between the walls and over the top of the concrete vault was filled with earth, graded, and then paved to create the 25-foot wide roadway over the bridge. The bridges' "natural" appearance and careful integration into their respective environments are the result of the visionary work of the Park Service's structural and landscape architects, and the careful craftsmen who were contracted to build them. Each construction plan followed strict guidelines to preserve the natural landscape, and the plans were carefully checked on location to ensure that they would "fit the ground."

Extraordinary measures were taken to minimize damage to the parks’ scenery. Blasting had to be limited (even though this was a hardship in the often sloped and rocky mountain terrain), and trees and other vegetation were left standing whenever possible. Debris was disposed of as inconspicuously as conditions allowed. Sites where rock was quarried and fill dirt excavated were located out of sight of the roadway in areas that would not be permanently scarred by the removals. The construction camps were set up in places that could tolerate hard use and be successfully restored. After construction was finished, damaged slopes were smoothed and rounded and then replanted with native species matching those in the area (often provided by the park's plant nursery). To properly admire these long-lived historic structures in their very different, well-restored landscapes, you must get out of your car. Traveling north through Sequoia National Park, you'll come first to the Marble Fork Bridge, which carries the Generals Highway over a lively, boulder-strewn branch of the Kaweah River. Just beyond the road turning into the Lodgepole area, you'll cross the bridge and then immediately turn left into the Lodgepole Picnic Area. Importantly, this fine spot for lunch or a snack also offers easy access to the river and an excellent view of the bridge from the bank, or, when conditions permit, from in the stream itself.

The Marble Fork Bridge spans a distance of 45 feet and is beautifully proportioned to its intimate forested setting. Outstanding masonry work melds the bridge with its landscape. The native stone was selected to match the surrounding rocks, and precisely cut to the architect's specifications to create a natural look. Drive about another mile ahead and you'll come to the waterway crossed by the 90-foot span of the Clover Creek Bridge. Here the terrain is wide open, with the stream slicing through sheets and slabs of bare granite. Walk over the bridge to enjoy the big views and marvel at how well this timeless, rugged structure suits its environment.

A small third "bridge," spanning Silliman Creek just beyond the Marble Fork bridge, is included in the Generals Highway Stone Bridges Historic District. Technically, this structure, which spans a distance of only 16 feet, is a culvert, not a bridge (which by engineering definition is over six meters in length). Nevertheless, even this minor construction, a reinforced concrete slab, features rubble masonry abutments and facing to harmonize it with the very rocky creek bed it traverses, and so provides another noteworthy example of Parkitecture. By the summer of 1935, the great vision of linking the two national parks and their iconic sequoias -- General Sherman and General Grant -- via a superbly scenic, easy to drive road had been realized, and on June 23, the newly-completed Generals Highway was dedicated to the public. Cars -- 669 of them -- drove in, from both the Sequoia and the General Grant park entrances, bringing 2,488 people to celebrate the great accomplishment. They met for the ribbon-cutting at the highway's halfway point: the panoramic Clover Creek Bridge. April, 2021

NOTE: See our related articles on enduring "Parkitecture" Treasures: Ash Mountain Entrance Sign, Hockett Meadow Ranger Station, Moro Rock Stairway, and Redwood Meadow Ranger Station |

Maps, Directions, and Site Details:

|

|

Directions:

Just west of Lodgepole in Sequoia National Park. From Visalia, take Hwy 198 east through Three Rivers to Sequoia National Park. Continue on the Generals Highway past the Giant Forest to Lodgepole (about 21 miles from the park entrance). Immediately past the entrance to Lodgepole, you will come to the Marble Fork Bridge. Just after the west end of the Marble Fork Bridge, turn left into the Lodgepole Picnic Area; park and walk down to the river for good views of the bridge. Back in your vehicle, you will cross the Silliman Creek Culvert shortly after you leave the Lodgepole Picnic Area, continuing northwest. About one mile farther on the highway is the Clover Creek Bridge. Just after the west end of the Clover Creek Bridge there is a parking area on the left side of the road with good views. |

Site Details:

Environment: Mountains, Sequoia National Park, historic bridges over Clover Creek, Marble Fork of the Kaweah River, and Silliman Creek (culvert)

Activities: architecture and landscape architecture study, birding, history, photography, picnicking (at Lodgepole Picnic Area), water play (at Lodgepole Picnic Area, Marble Fork)

Open: Sequoia National Park is always open, weather permitting, unless closed due to emergency conditions; park entrance fee

Site Steward: National Park Service-Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks; 559-565-3341; www.nps.gov/seki

Opportunities for Involvement: Donate, volunteer

Links: National Register of Historic Places documentation: https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/78000284; www.nps.gov/seki/learn/historyculture/generals-highway.html

Photos for this article by: John Greening and Laurie Schwaller, and courtesy of: copyright Jonathan Irish, Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress; National Park Service; Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Archives.