HERBERT WETLAND PRAIRIE PRESERVE

|

The Mysterious Life of Vernal Pools

by Rob Hansen Just beneath the surface of the Herbert Preserve is a layer of very tough clay, called durapan, which is largely impervious to water. Plentiful rains can create springtime vernal pools atop this clay in the low "hogwallows" between the preserve's hummocky mima mounds. Typically at their largest from March to May, the pools gradually evaporate as the hot weather comes on. During their short lives, these vernal pools provide a rich aquatic habitat that is almost unique to California, and home to some amazing life forms. For example, the pools support paper-clip-sized fairy shrimp. These are crustaceans, like shrimp in the ocean, but the fairy shrimp are living in the Central Valley desert, far from the sea. During most of the year, when the pools are dry, the shrimp are not alive. They are enclosed in tiny, durable cysts, like hard little eggs, waiting in the arid clay for rain to fall. As soon as there's enough water, the cysts wet and hatch. If their vernal pool is deep enough long enough, the hatched shrimp will live for a brief month or two, during which they will mate and lay eggs. The eggs will hatch and develop into adults, and the adult shrimp will encase themselves in their cysts once more as the pools dry again into clay. |

|

Fairy shrimps' ancestors lived in the world's salty ocean. As land began to form above the ocean, water

on the land turned fresh, and some shrimp ancestors adapted to living in

it. Creatures -- such as fish --developed that

could eat these little shrimp.

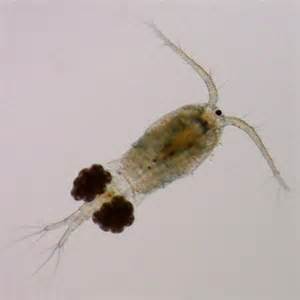

But no fish live in vernal pools, because these unusual freshwater ecosystems are filled by rain and have no connection to a stream. So the tiny shrimp thrive in the vernal pools. They are in a sense celebrating life as it was on the planet before there were fish to eat them. If we put these fairy shrimp back into the ocean now, they'd be fish snacks in moments. The vernal pools also house miniscule clam shrimps and very small crustaceans called copepods, which most people call "Cyclops" because they look as if they have a little red eye in the middle of their head. Thus, the vernal pools create amazingly rich storehouses of food and provide wonderful meals, not for fishes, but for many different kinds of birds.

|

|

The pools also host the western spadefoot, a toad reminiscent of a science fiction creature. The hind foot of this intriguing amphibian is equipped with a spade, a very tough, callused little black triangular area that the toad uses to dig in the mud.

For most of the year, though, these toads aren't digging. They're living underground in a state that is very near death, rather like suspended animation. Their heartbeat is near zero. They are barely respiring. When they go underground, they have to bring with them in their body tissues all the moisture needed to sustain themselves for sometimes over a year, but usually from about May to November. Imagine that you're a toad and it's November, and the first winter storm is arriving in the Valley. In your little chamber below the dry bed of a vernal pool, you are listening for the sound of raindrops. Spadefoot toads don't just respond to the soil getting moist; they literally have to hear the rain falling long enough to feel assured that there will be enough water to allow them to break out of their little tombs, get back above ground, find another toad, and mate and lay eggs. Suddenly, almost miraculously, as soon as the dry pools get wet again, adult toads are swimming about, looking for a mate. They give a "brrrrrrrrrt" call, like the sound of running your finger over the tines of a metal comb (Spadefoot Toad Mating Call).

When the toads are calling, it's a good indication that they're going to have a successful year. Their eggs will hatch, and their tadpoles will grow, lose their tails, and turn into adults. And then, when the all the water has evaporated from the vernal pools, the mud that was solid, smooth like a bathtub bottom, will begin to dry and shrink and crack. And in those little cracks, you can see the heads of little toads backing down with the spade on their hind foot digging, digging, digging to bury themselves in the mud. FAIRY RINGS In the springtime of wet years, hundreds of vernal pools may form in the Herbert Preserve, attracting myriads of birds and reflecting the snow-capped Sierra in their still surfaces. The water arrives from the clouds, falls to the ground, and fills the pools. But the water doesn't sink into the ground because of the impermeable clay layer at the surface, and it doesn't drain away down a channel because the land is comprised of mounds and swales. Instead, the water disappears by evaporation. Once a pool has formed, it will be at its maximum size for a fairly short time; then the water will begin to evaporate, and the shallow pool will slowly shrink until it's all dry. Several flower species have adapted to this shrinking progression: some like very shallow water, others prefer it a bit deeper, and still others like to grow just at the edge of the pool. As the pool recedes throughout the spring, rings of these colorful flowers follow the retreating water. The Herbert Preserve's location in Tulare County, near the southern, desert end of the Central Valley grassland, limits the variety of vernal pool flowers that can grow here. But when rain is abundant, we get to see rings of Downingia, a beautiful little purple flower; rings of tiny yellow "goldfields"; and in the years when things work their very best, small rings of white vernal pool "popcorn." The colorful, delicate fairy rings don't last long, and they need a good wet year to form at all, so you must time your visit carefully to witness these magical floral displays at their loveliest. February, 2015 |