PEAR LAKE SKI HUT

"This historic cabin is available to the public from December to April (weather, snow and trail conditions may change closure date). The advanced level ski-snowshoe trail offers a chance to explore the beautiful wilderness of the Sierra Nevada mountains during the winter months with a cozy cabin waiting for you at the end of your day." -- Sequoia Parks Conservancy

"Compared to other California ski huts, . . . Pear Lake Ski Hut is remote, situated 6 miles from the trailhead. Reaching the hut in winter is no easy feat. But for those willing to make the slog in, the vast wintertime playground that surrounds the hut holds bountiful wintertime rewards." -- outdoorproject.com

"If a ski descent down 11,328-foot Winter Alta [AKA Skiers Alta] doesn't get you grinning ear-to-ear, we're not sure what will. . . [N]orth of often climbed Alta Peak, sharing the same ridgeline . . . it's one of the better intermediate backcountry ski runs in the Sierra. High above tree line, this north-facing bowl holds great snow during winter and offers over 2,000 feet of vertical along with stellar views and a backcountry ski hut to boot." -- Aron Bosworth"

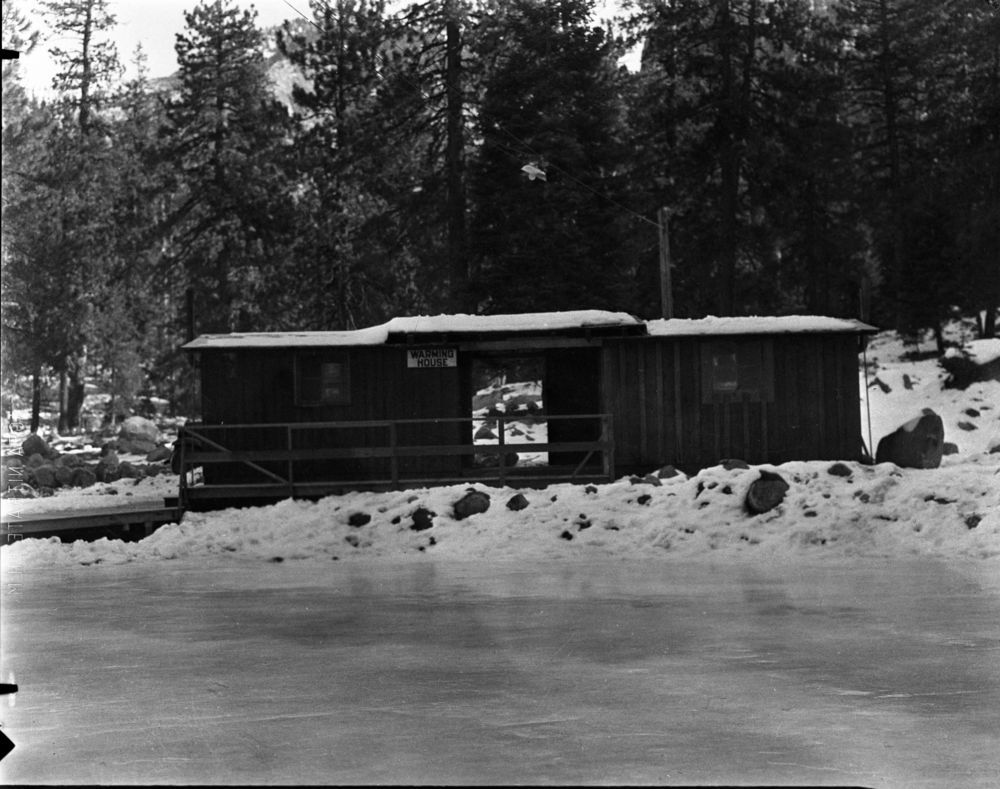

The ski hut remains hidden from view within the Pear Lake drainage until you're nearly on top of it. The hut sits on the edge of a cluster of trees in the drainage one-third of a mile down hill from Pear Lake proper." -- Aron Bosworth

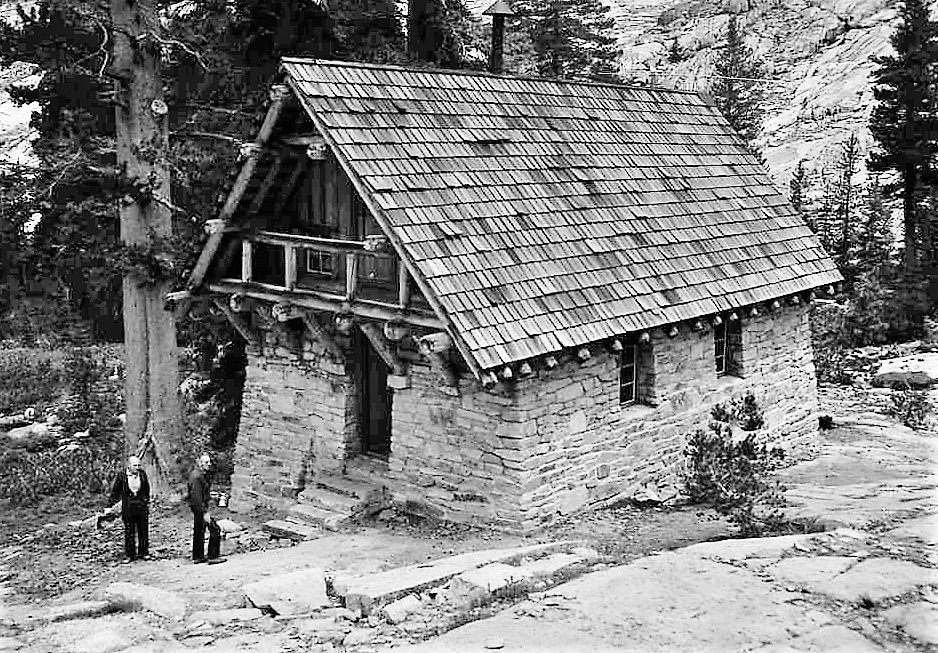

"One of the snow surveys we did four times a year was the Pear Lake survey . . . . We would stay at the Pear Lake ski hut, . . . a handsome stone structure that looks like an enchanted cottage from a Nordic fairy tale. . . . [I]t's the only backcountry cabin in Sequoia available in the winter for public use, on a reservation basis." -- Steve Sorensen

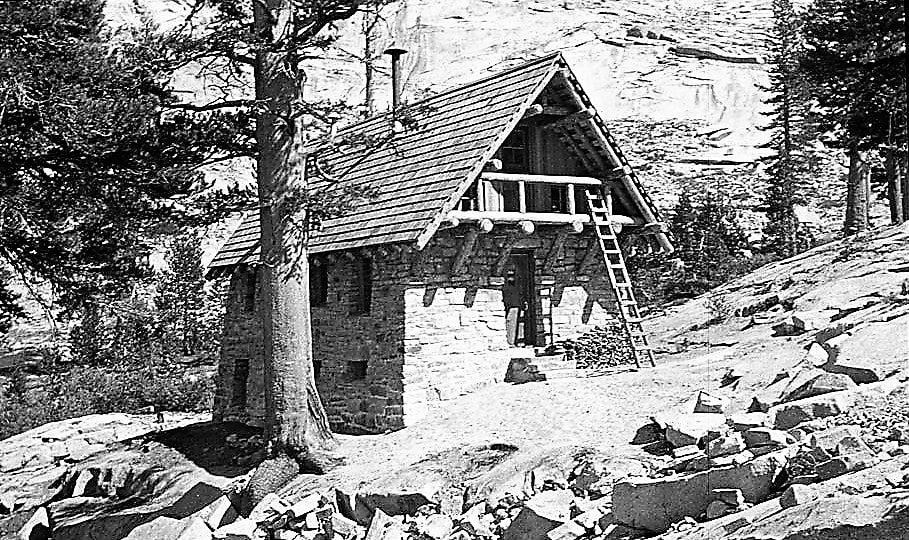

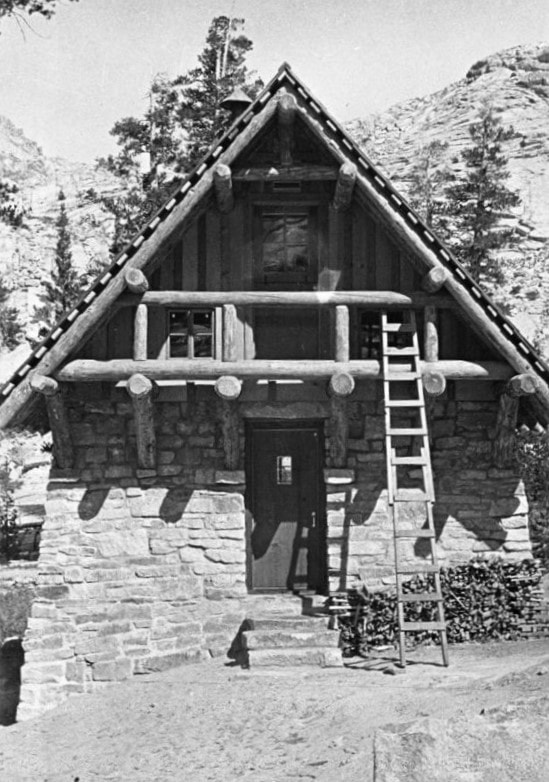

“Standing near timberline in a spectacular alpine setting, the [Pear Lake] shelter’s design purposely avoided drawing attention to itself. Not only did the use of natural materials cause the building to harmonize well with its natural surroundings, but the design of the building made it appear considerably smaller than it actually was. . . . [T]he oversized windows in the sidewalls created an optical illusion that reduced the apparent size of the structure." -- National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1977

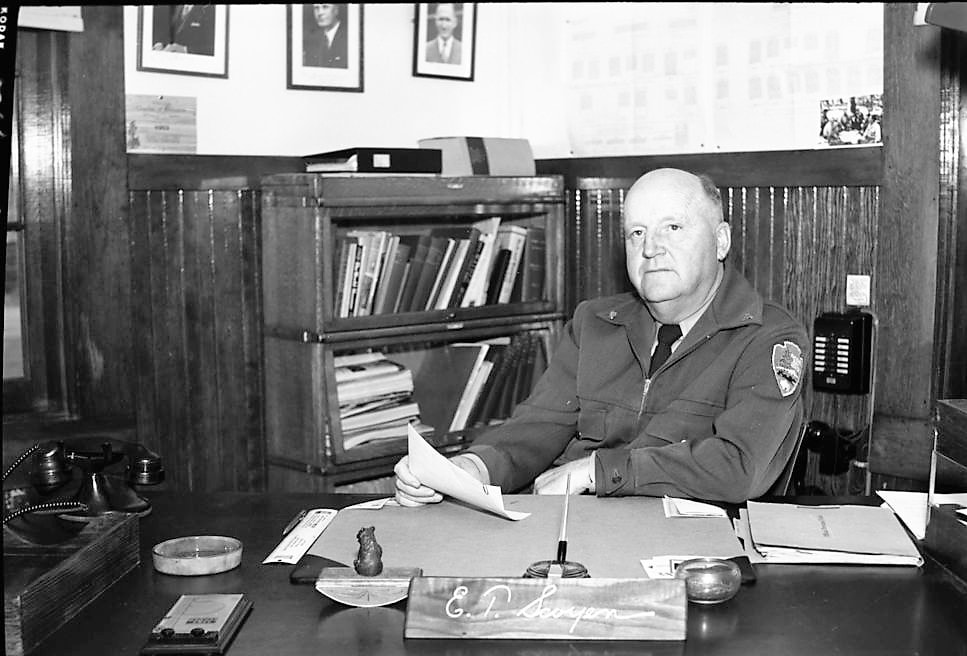

"The Project at Pear Lake will require a crew of 20 CCC enrollees for a period of 100 working days. The stone masonry will require 150 days of skilled labor at a cost of $80. Packing of 130,000 lbs of materials will cost $1,960. Packing labor will be an additional 175 man-days @ $5.” -- Sequoia National Park Superintendent Eivind Scoyen, July 20, 1939

"The masonry structure, which measures 17 by 30 feet, seems to rise naturally out of the bedrock." “Nearly all of the exterior materials used in the structure are of natural origin. The masonry walls were constructed of irregular native granite and battered to increase the resemblance to nature. The roof rafters and brackets were constructed of pine logs cut in the immediate vicinity. . . .The roof was shingled.” -- National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1977

CCC conifer log construction; Sequoia N.P. restoration crew worker, 2014 CCC conifer log construction; Sequoia N.P. restoration crew worker, 2014

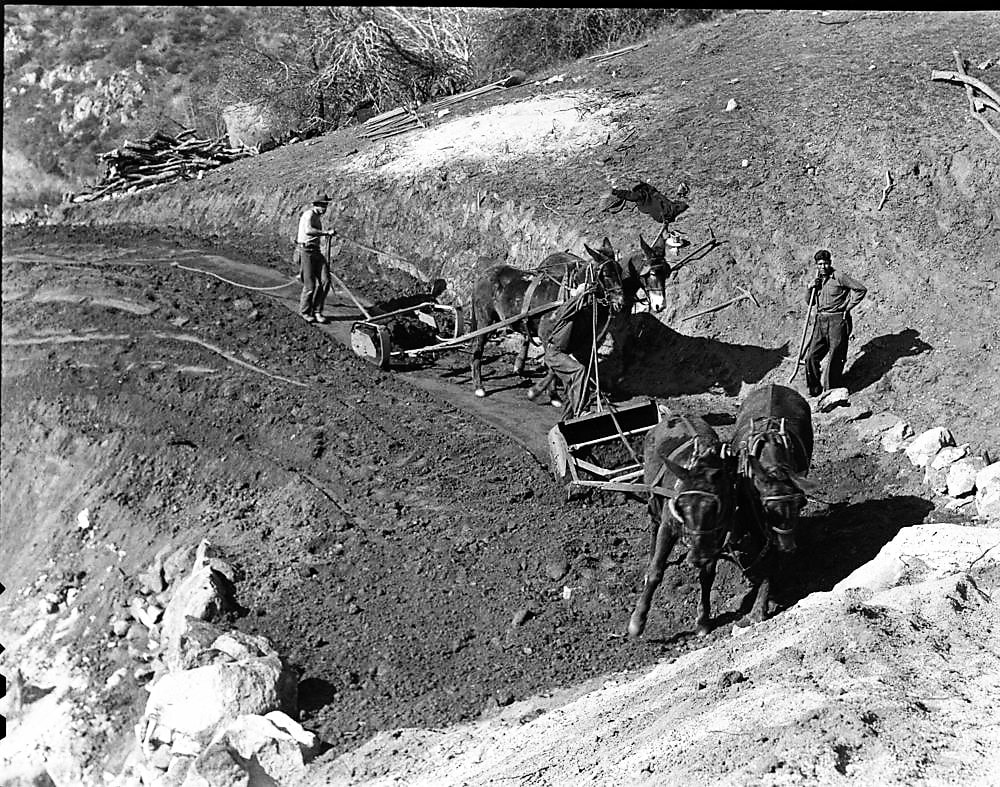

"A stub camp has been established at Pear Lake and work now consists mainly of constructing a section of approach trail (1600 feet). Logs will be cut to season over the winter, and all materials brought to the site as soon as possible." -- Sequoia National Park Superintendent Eivind Scoyen, August, 1939

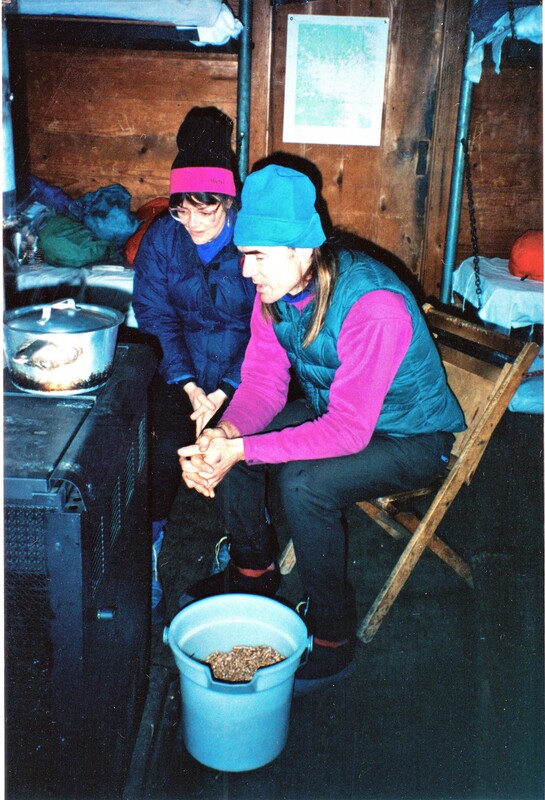

“The interior is divided into two portions—a large room which comprises over three-quarters of the interior and serves for sleeping and cooking, and a narrow chamber at the rear which is further subdivided into a storage chamber and a chemical toilet closet . . .One of the roof gables shelters a second-story balcony.” – National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1977

"Wood pellet heating stove with fuel – this was pretty awesome, we were able to hang anything that got wet just above it to dry. It was quite cold when we were out there, so having this was a luxury." -- beyondlimitsonfoot.com

"As you would expect, hanging out in the hut telling stories and playing cards with the hutmaster and other outdoor enthusiasts was a great experience!" -- highsierratopix.com

|

"Good morning, everyone,” he calls from the kitchen area. “It looks like we’re in for a perfect Pear Lake day!”

Tucked into a glacial valley below one of the most prominent peaks in Sequoia National Park, Pear Lake offers a rare opportunity of a true backcountry experience within front country hiking range. The sparkling, high alpine lake, set directly under 11,208 ft. Alta Peak’s rugged cliffs, is a day hike or overnight backpack trip worth every moment of the six-mile trek on foot, skis, or snowshoes. And its historic winter ski hut/summer ranger station is a treasure to be remembered. The routes to Pear Lake are just as special as the hut itself. In summer, the Lakes Trail passes three small alpine lakes, each nestled into its own high-altitude scenery. The Watchtower segment, its popular summer portion of the trail, takes you through a cliff-hugging section with a spectacular view of Sequoia National Park’s mountain ranges.

Starting from 7,200 feet elevation at the park's Wolverton trailhead, both routes are rigorous hikes with a 2,000-foot vertical rise to reach the Pear Lake Hut. On the Lakes Trail, summer campgrounds at Emerald and Pear lakes provide the opportunity to make it an overnight adventure.

In winter, the Watchtower portion is impassable and the Lakes Trail takes all the traffic up one final pull called “The Hump” to the ski hut. The sight of the hut, standing at the edge of a grove of lodgepole pines and surrounded by granite highlands, welcomes the visitor to a true alpine experience of historic significance.

The winter hut ski experience came late to the Sierra Nevada. Born from the recreational use of sheep and dairy cattle herders’ huts in the alpine regions of Europe, the concept formally arrived in the northeastern United States and Canada in the 1880s. From there, it spread to the Rocky Mountain regions and finally, to California’s Sierra Nevada. It took the financial boom years of the roaring 1920s to make it happen. As America’s National Parks began encouraging their concessionaires to increase their summer services to accommodate rapidly increasing numbers of summer visitors, California’s Sierra Club began demanding that winter sports be included in their services. Both Yosemite and Sequoia national parks responded by installing small rope ski tows and small ice-skating rinks in their tourist areas, but the concept of wilderness skiing was just a talking point. It wasn’t until until the National Ski Association’s 1936 convention openly castigated the Park Service for effectively keeping winter recreation a low priority in its parks that Sequoia National Park Superintendent John R. White promised to start planning the construction of ski huts in its wilderness.

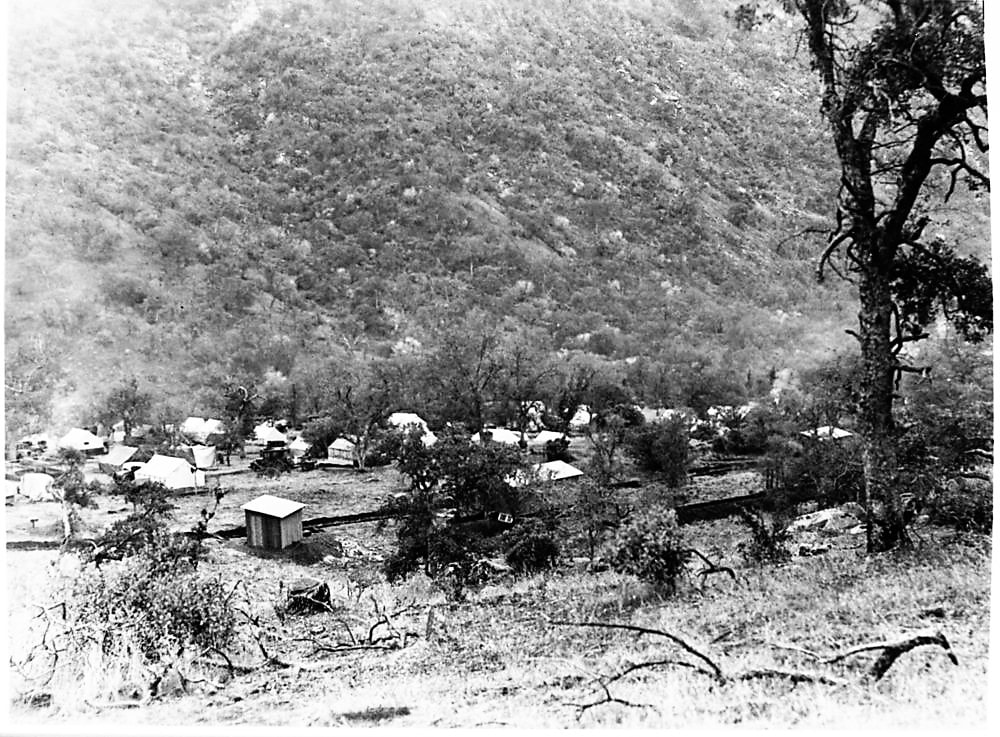

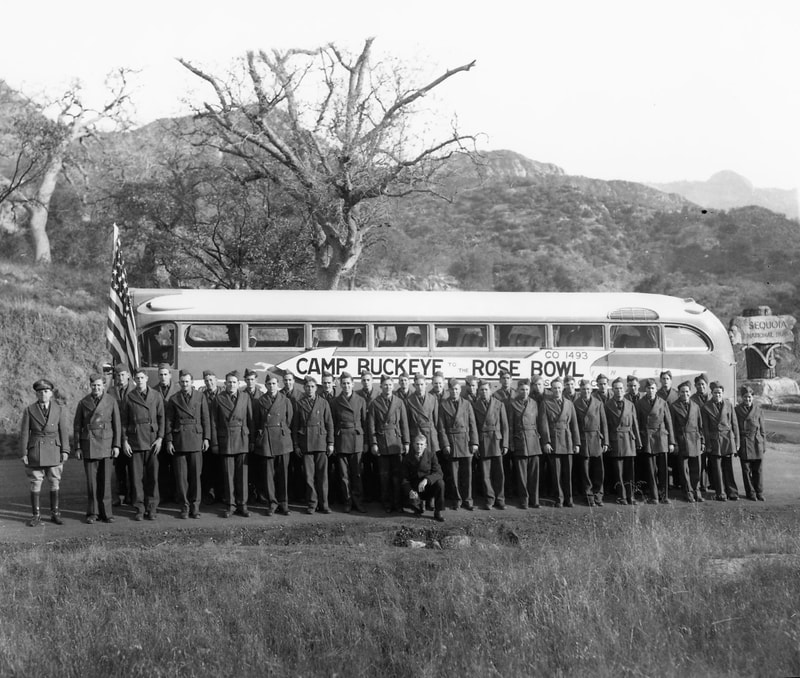

It wouldn’t be easy, for the nation was in the throes of the Great Depression, and any construction depended on a workforce from the federal Civilian Conservation Corps. But it wasn’t until 1938, when the CCC program was winding down, that a plan was finally approved. Then, after April 29, 1939, when the CCC did fund $3,000 for construction of three shelter cabins in Sequoia’s backcountry, the park’s new superintendent, Eivind T. Scoyen, immediately made some changes. Urging a “cautious approach to the development of an extensive system of trail shelters in Sequoia,” Scoyen put the focus on just one hut at Pear Lake and revised the building plans to a cheaper, one-and-a-half-story, two-room, low-to-the ground structure. In August, a stub camp of the Three Rivers Camp Buckeye crew was opened. The crew had already done much work on Sequoia National Park’s truck trails, the Generals Highway, and buildings at Ash Mountain headquarters. But the Pear Lake Hut was a new experience. Following the Park’s architectural focus that emphasized the relationship between a structure and its natural environment, the wood and stone hut was placed at the edge of a grove of lodgepole pines where it blended in with its surroundings. Nearly everything on the exterior of the building came from the surrounding area, and the work was handcrafted as much as possible.

By October an access trail had been built and all the local sand, rock and logs needed gathered. Fifteen percent of outsourced building materials had been packed in to the site, and preliminary work on the site was begun. Then, with the onset of snow season, work stopped. In July, 1940, work began again with a 20-man CCC crew. Scoyen’s monthly reports were terse and noted growing problems. “Due to inexperienced labor, this project may not be completed,” he wrote in August. In September: “Cold weather may prevent the completion of this project this year.” And in October, after completion of all the rock work, except for one corner, he reported “Work has been discontinued until next year." The next year was no easier. “The snow is still deep in the backcountry, even JO Pass is not open as of the end of June,” Scoyen reported. Work wasn’t restarted until August, with the completion of the masonry, and plate logs, porch brackets and beam logs in place. It wasn’t until September 29, 1941, that the building was declared completed. And just in time. “The CCC program is rapidly coming to a halt,” Scoyen noted. “From a high of 7 camps in the park, only two are operating and one of these is about to leave.”

The Hut was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 5, 1978. Its nomination form cites two main contributing factors. One was the structure’s intensive levels of hand labor and high levels of craftsmanship that made it a particularly appropriate memorial to the CCC program. The second was its example as “the best of National Park Service rustic architecture . . . one of the most environmentally successful alpine structures ever designed by the NPS.” It took time for the Pear Lake Hut to become reality. Careful time to make it the special treasure it remains. As you go out from its seemingly indestructible basic comforts to ski or hike the inviting granite slopes surrounding it, you might take time to pause and look back before the hut melds into the landscape. And marvel, that there is a place you can go where human enterprise and nature can still be one.

March, 2022

|

Maps, Directions, and Site Details:

|

|

Directions:

Pear Lake Ski Hut/Winter Hut/Ranger Station is accessible via the Lakes Trail, which begins at the Wolverton picnic area parking lot in Sequoia National Park. From Visalia, drive east on Hwy 198 through the town of Three Rivers to the Park entrance (fee). Follow Hwy 198 (called the Generals Highway in the Park) up the mountain to the Giant Forest. Shortly after passing the winter parking area for the General Sherman tree, turn right onto the road to Wolverton. The trailhead is on the north edge of the east parking area, elevation 7,280'. The trail ascends a steep six miles to the Pear Lake area at 9,200', where a ~1/3 mile spur trail leads to the hut. The snow season trip to the hut, which roughly follows the Hump portion of the trail, is for experienced backcountry skiers and snowshoers; winter conditions are potentially very dangerous. Advance reservations are required. For site details and reservations, see https://www.sequoiaparksconservancy.org/pearlakewinterhut.html. In summer, the hut serves as a Sequoia National Park backcounty wilderness Ranger Station and houses Park personnel only. |

Site Details:

Environment: Mountains, conifer forest near timberline, elevation 9,200 feet, in Sequoia National Park*

Activities: architecture study, backpacking, hiking, history, photography, skiing, snow shoeing (NOTE: The hut can be visited only by foot/ski/snowshoe trail in winter; stock is permitted on the Lakes Trail in summer, for day use only, and never on the Watchtower portion.)

Open: Sequoia National Park is always open, weather permitting, unless closed due to emergency conditions; park entrance fee; Wilderness Permit required for all overnight trips; winter hut use is by advance reservation only via Sequoia Parks Conservancy. In summer, the hut serves as a backcounty wilderness Ranger Station. Note: Park Ranger Stations serve as residences for rangers and backcountry crews. Therefore, while you may knock on the door, please respect the occupants' privacy. Knock on the door when park employees are present if you need assistance or have information to report (e.g., wildfire, hazardous conditions, etc.). You may also leave a note.

Site Steward: National Park Service-Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks; 559-565-3341; www.nps.gov/seki; Pear Lake Winter Hut is managed by the Sequoia Parks Conservancy; 559-565-4251; https://www.sequoiaparksconservancy.org/pearlakewinterhut.html. In summer, the hut serves as a Sequoia National Park backcountry wilderness Ranger Station

Opportunities for Involvement: Sequoia Parks Conservancy (SPC) membership; donate, volunteer

Links: National Register of Historic Places documentation: https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/78000285

*The geology of the Pear Lake environment is in many ways visible and ongoing: Pear Lake is a glacial lake in a small basin under the north face of 11,208-foot Alta Peak, rimmed by vertical cliffs to the south and west that were eroded and sculpted by glaciers as they periodically advanced and receded over time. Before the glacial period, Alta Peak was a large dome of intruded granite formed from cooled molten rock miles below the earth's surface. This granite pluton was exposed with the uplift and erosion of the Sierra Nevada starting nearly 10M years ago.

Today the visitor can see the remaining southern portion of the glaciated dome of Alta Peak, as well as remnants of the glacial sedimentary deposits from eroded bedrock at its base. There are also bedrock surfaces "polished" by the advancing glaciers, and even boulders that were transported long distances on glaciers and left stranded after the glacier receded. Weather related erosion continues today with rockfalls and landslides visible beneath the cliffs. -- Laurel Di Silvestro, geophysicist

Photos for this article courtesy of: David Baselt; beyondlimitsonfoot.com; Ayelete Bitton; Aron Bosworth; Alice Kao/backcountrycow.com; Laile DiSilvestro; Laurel DiSilvestro; The Fresno Bee; Kevin Gallagher/7Trails Photography; Louise Jackson; Jennifer Carr Photography/jennifercarrphotography.com; jessieonajourney.com/April B. photo; myendlesswinter.com; National Park Service/Rick Cain photo; petesthousandpeaks.com; roamtheatlas.com, rove-met.com; Thor Riksheim/NPS; Ron Rothbart; Greg Scarich; Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks Archives; Sequoia Parks Conservancy; Aaron Slaven; snowymonk.blogspot.com; Reiner Stenzel; Johnnie Chamberlin, TrailsOfArkansas.com; tillthemoneyrunsout.com; Ryan Underhill; and Sarah Vaughan/Two Outliers