THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION SHELTER

ON MOUNT WHITNEY

|

|

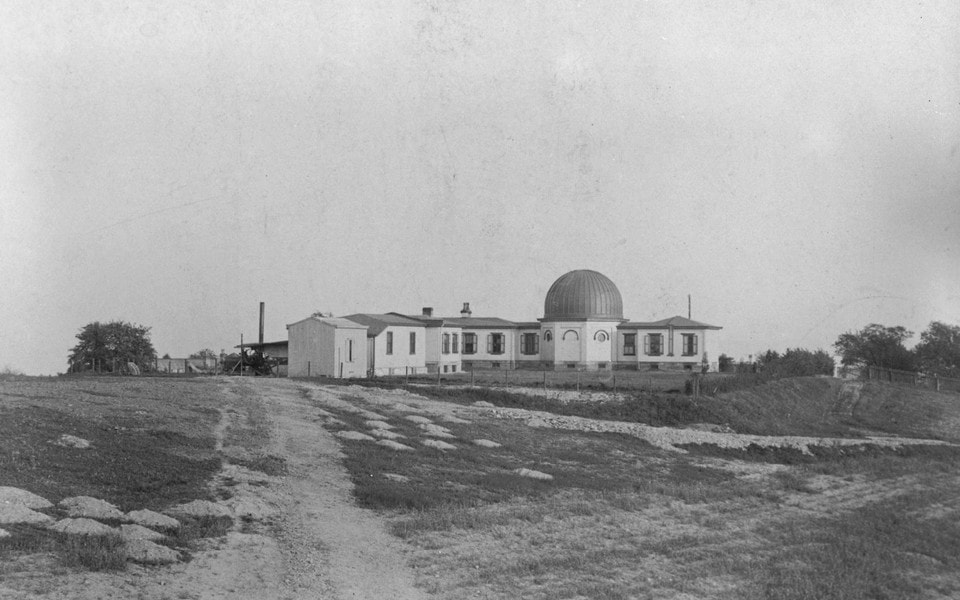

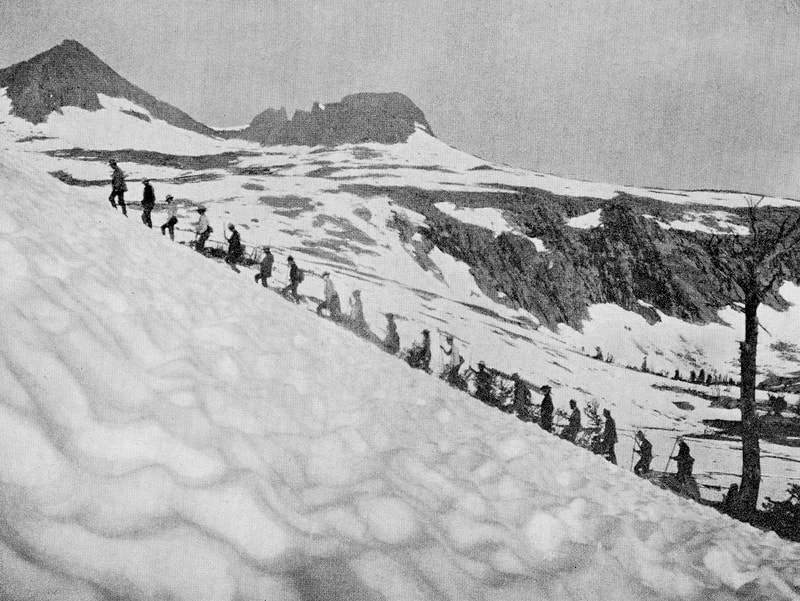

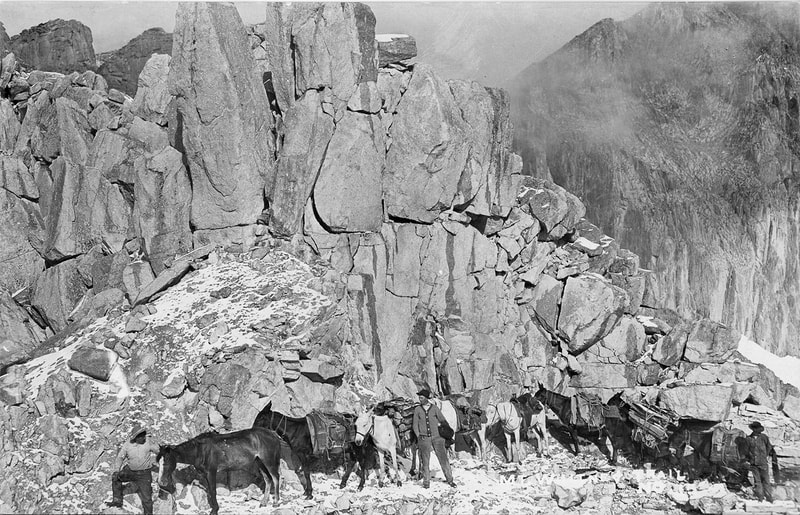

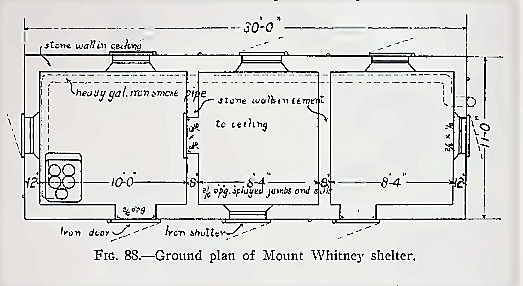

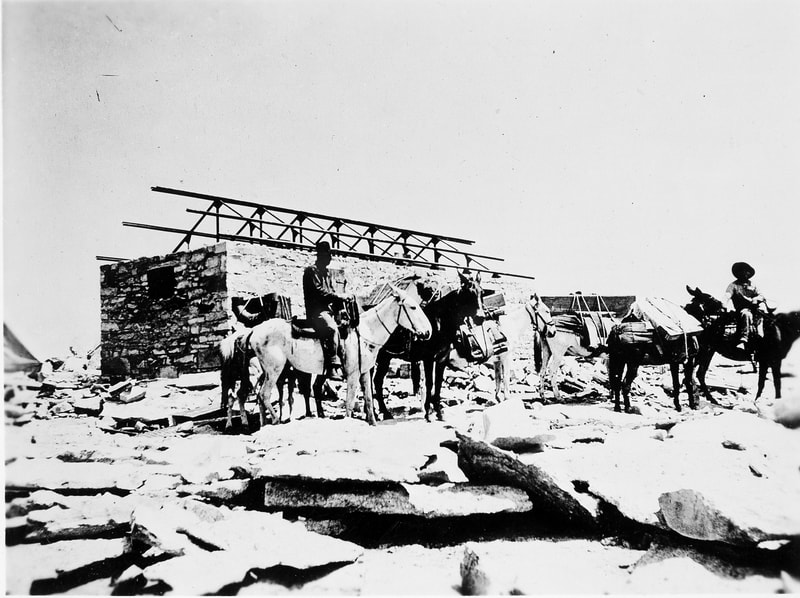

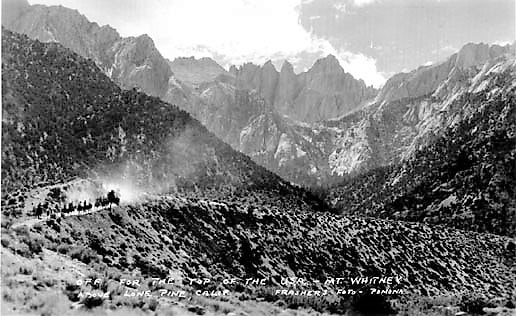

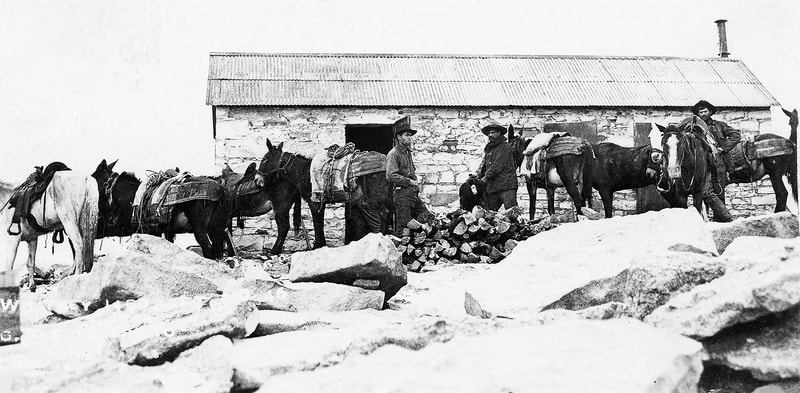

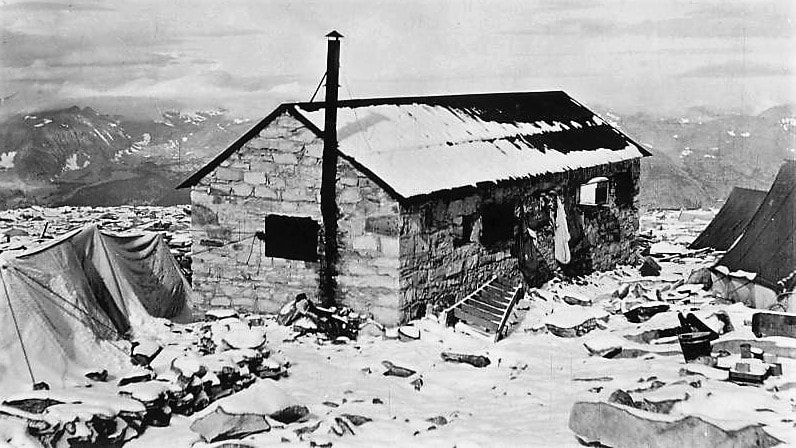

Science and Shelter at the Summit by Laurie Schwaller Mt. Whitney's distinction as the highest peak in our 48 contiguous states has made it a hiker magnet for almost 150 years. It also made it an astrophysicist magnet that drew a number of world-renowned scientists to its summit in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was the scientists who, in 1908-1909, were responsible for the design and construction of the Smithsonian stone hut that continues to offer shelter and photo opportunities to the tens of thousands of trekkers striving to reach the top each year. |

Maps, Directions, and Site Details:

|

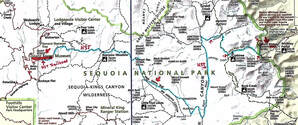

Mt. Whitney lies on the boundary of Sequoia National Park and Inyo National Forest. Permits are required to hike in the Mt. Whitney Zone. Hikers are advised to carry crampons and ice axes when snow and ice may be on the trails. Those on the summit are warned against seeking shelter in the Smithsonian hut during lightning storms.

The shortest and most popular route to the summit is a 10.7 mile trail from Whitney Portal, 13 miles west of the town of Lone Pine on the east side of the Sierra, via Hwy 395. |

Permits: About 30,000 people per year want to hike Mt. Whitney, so hikers must secure a permit from the Forest Service in order to enter the Mt. Whitney zone. Permits are required year-round, for both day and overnight use, and a quota system is in effect between May 1 and November 1. Applications to reserve a backpacking trip on the Mt. Whitney trail or a day hike in the Mt. Whitney Zone are accepted in the Mt. Whitney Lottery from February 1 through March 15. Any space left over after those dates will go on sale April 1 at 10:00 a.m. Go to https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/inyo/passes-permits/recreation/?cid=stelprdb5150055 for Inyo National Forest permit and trail information. Wilderness Office Information Line: 760-873-2485. Reservations can be made through www.recreation.gov.

|

Other routes to Mt. Whitney are less heavily used, but require a much longer hike to reach the summit. To start from the west side, the High Sierra Trail leaves from Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park and is about 60 miles (taking a minimum of 6 hiking days) one-way. A Sequoia National Park wilderness permit is required. https://www.nps.gov/seki/planyourvisit/whitney.htm https://www.nps.gov/seki/planyourvisit/high-sierra-trail.htm https://www.nps.gov/seki/planyourvisit/wilderness_permits.htm |

Environment: Mountains, summit of Mt. Whitney, Sequoia National Park (NOTE: the Smithsonian shelter can be visited only by foot trail; trailhead elevation is 8360', summit elevation is appprox. 14,500'.)

Activities: architecture study, backpacking, birding, camping (below the summit), hiking, history, photography, wildlife viewing

Open: Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks are always open, weather permitting, unless closed due to emergency conditions; park entrance fee; Wilderness Permit required for all overnight trips

Site Steward: National Park Service-Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks; 559-565-3341; www.nps.gov/seki

Opportunities for Involvement: Sequoia Parks Conservancy (SPC) membership, donate, volunteer

Links: National Register of Historic Places documentation;

https://www.nps.gov/seki/planyourvisit/wilderness_permits.htm:

https://www.mulemuseum.org/;

https://www.mulemuseum.org/building-mount-whitney-trails.html

https://www.mulemuseum.org/the-mount-whitney-trail.html

The Smithsonian Shelter was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 8, 1977, because it is "a monument to the difficulty of high altitude research in the period before prolonged human flight was possible."

Photos for this article by: D. Appleton & Co., publ., Essays in Astronomy, 1900, public domain; Gary Ballentine, granitecliffs.com; base-medical.com; Bob Burd; Andrew Cox, backcountrysights.com; Arturo Crespo; Dark Sky Photography/Eastern Sierra Observatory; Bryan Feller; Google Earth; Alvis E. Hendley; Matthew Karsten, expertvagabond.com; Andy Lewicky, sierradescents.com; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Hector Macpherson Jr., in Astronomers of Today, 1905, public domain; Chuck McKeever; Meteorological Office Digital Library of Archives, in Symons's Monthly Meteorological Magazine, June, 1876; My Old Tulare County Pics; NASA/JPL-Caltech; NASA, Watch the Skies; National Park Service; National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, CCO, object #NPG.92.61; OAC/UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library, Portrait Collection, photograph by Buck, Washington, D.C.; OwensValleyHistory.com; portrattarkiv.se, sj9PGLAlnmUAAAAABfm2g; Photographs by John Reece, copyright 2018; Andrew Piotrowski; Thor Riksheim/NPS; Matthew Saville, astrolandscapes; jon-schmid; Brandon Sharpe, brandonexplores.com; Smithsonian Institution Archives; Smithsonian Libraries; Smithsonian National Museum of American History; Brad Spiess, ihikesandiego.com; stock cover image; The Eastern California Museum, Frederick G. Harvey photo; University of California Santa Cruz, Special Collections; University of Pittsburgh Library System Digital Collections, George W. Tea photo; University of Southern California Libraries and California Historical Society, Hervey Friend photo; whitneyzone.com forum; Daniel and Timea K. Zilcsak