Through twelve thousand or more years of existence in what is now California, humans knit themselves to nature through their vast knowledge base and practical experience. In the process, they maintained, enhanced, and in part created a fertility that was eventually to be exploited by European and Asian farmers, ranchers, and entrepreneurs . . . ." -- M. Kat Anderson

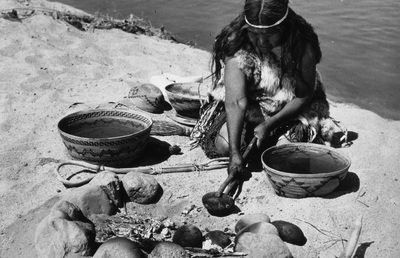

"Settlement by people culturally akin to the Yokuts probably began about 7,000 years ago. . . . Four or five thousand years ago, these forebears of the Yokuts adopted a method of acorn leaching which allowed them to tap a vast new food supply." -- William L. Preston

"It is difficult to say whether the Yokuts intentionally engaged in plant domestication, but it is clear that they applied some of their horticultural knowledge to foster growth of favorite food plants." -- William L. Preston

"Food taboos and totem relationships protected certain animals from overhunting, and land rights protected especially productive areas from over-exploitation." -- William L. Preston

"The Yokuts were true conservationists, and never took more than they could use." -- Annie Mitchell

"Most tribes had legends that vividly told of the consequences that would befall humans if they took nature for granted or violated natural laws: . . . one must interact respectfully with nature and coexist with all life-forms." -- M. Kat Anderson

"Human impacts on the natural systems were real and significant, but an approximate equilibrium had been established that later residents of the region misperceived as purely natural." -- Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed

"Their life and customs are those of Nature herself, who with a liberal hand supplies them with wild quadrupeds, fowls, fish, and nourishing seeds, with which they meet their only need." -- Jose Bandini, 1828

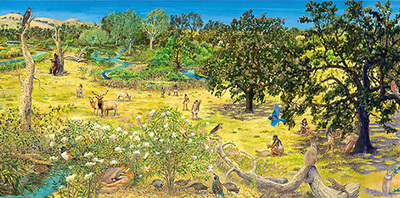

"Staring in awe at the . . . extensive beds of golden and purple flowers in the Central Valley, [John] Muir was eyeing what were really the fertile seed, bulb, and greens gathering grounds of the Miwok and Yokuts Indians, kept open and productive by centuries of carefully planned indigenous burning, harvesting, and seed scattering." -- M. Kat Anderson

". . . [T]he Western Mono established over time a line of winter village sites in the middle foothills of the west slope [of the Sierra Nevada]. Several of these village sites, including Hospital Rock and Potwisha along the Middle Fork of the Kaweah River, are now within Sequoia National Park." -- Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed

"The largest known Potwisha village apparently occupied the narrow river terrace along the Middle Fork of the Kaweah now known as Hospital Rock." -- Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed

Photos for this article by: John Greening, Laile Di Silvestro, Laurie Schwaller; and courtesy of the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Archives; L. Gassaway; and F. Latta and A. Barr, from Kern River Historical Reenactment, Tulare County Office of Education; illustrations by Andrea Cooper and by Doug Hansen, courtesy of Sequoia Riverlands Trust; mural by Ben Barker courtesy of Exeter Chamber of Commerce |

NATIVE AMERICAN CONSERVATION

Environment: Valley, Foothills, Mountains

Activities: birdwatching, educational activities, hiking, historic and pre-historic sites, photography, wildlife viewing Open: Most of these sites are open year-round, weather permitting Site Stewards: Native American sites exist throughout Tulare County; they are on land stewarded by the National Parks, the National Forests, the Bureau of Land Management, the Archaeological Conservancy, Sequoia Riverlands Trust, and many private landowners Opportunities: Volunteer opportunities are available with all of the above organizations. Links: California Indian Basketweavers Association; Tule River Tribe; Lake Kaweah Heritage Visitor Center; Three Rivers Historical Museum; Tulare County Museum Books: 1) Challenge of the Big Trees by Lary M. Dilsaver and William C. Tweed (Sequoia Natural History Association, Inc., 1990) 2) Handbook of Yokuts Indians by Frank F. Latta (Bear State Books, 1949; 2nd edition, 1977) 3) The Men of Mammoth Forest by Floyd L. Otter (self-published, 1963) 4) The Sierra Nevada Before History by Louise A. Jackson (Mountain Press Publishing Co., 2010) 5) Tending the Wild by M. Kat Anderson (University of California Press, 2005) 6) The Way It Was by Annie Mitchell (Tulare County Historical Society, 1976) Directions: Maps and directions are at the bottom of this page. History:

The Story of Prehistoric Native American Conservation in Tulare County by Louise Jackson In the beginning, there were no fences. There were only the trails of animals and people winding through the oak trees and swamplands, along rivers, up into the foothills and mountains, and across the dry, hummocked prairie of Tulare County.

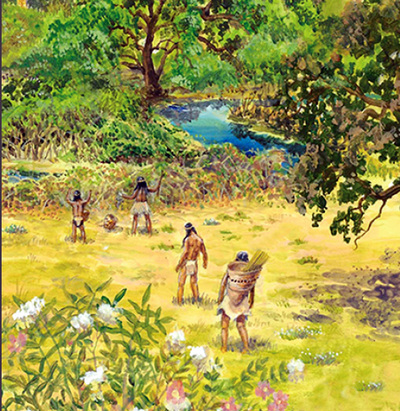

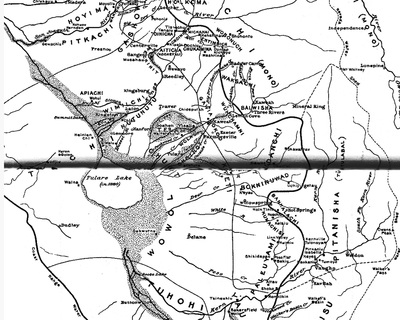

For thousands of years, migrants with different languages from distant lands walked those trails. They met each other, hunted, gathered, traded, and sometimes fought, moving often with the seasons and fluctuating climate. Intensely aware of the need to respect and conserve the natural world they depended on, they adapted to each change and prospered. Today, we often follow those same ancient trails but there is little to remind us of their vital past. They have been widened, straightened, paved and bent around property lines. The rich river-bottom lands have been flattened into fields. The small villages that dotted them have been replaced by towns and cities. The children of the ancient people are scattered now. Generations of new immigrants fill the land. By the time modern Europeans and Americans found their way to the rich Central Valleys of California in the 1850s and 1860s, two broad cultural prehistoric groups had broken into dozens of separate tribal entities. The lands of Tulare County were home to the Yokuts and Western Mono or Monache. Two sub-groups or tribelets of California’s great Yokuts nation settled along the lower waterways and alluvial plains of the Kaweah and Tule rivers. The Kaweah River’s Wukchumni and the Tule River’s Yaudanchi were descendants of generations of people who migrated east and south from Asia thousands of years ago. They shared a common basic language, culture, and conservation skills. The first American adventurers to encounter them generally noted them as a peaceful, structured, and friendly people. Blessed with abundant valley and mountain resources, they engaged in few territorial battles, enjoying a culture of job specialization, cooperation, intertribal trade, tradition, gaming, revelry—and also strict taboos.

The most important practices and taboos were those that conserved the resources on which the Yokuts so closely depended. Nature was the basis for everything the Wukchumni and Yaudanchi did. They utilized natural features wherever possible, rather than creating new structures. They enhanced food sources by pruning and selectively cutting vegetation, rather than cultivating more plants. They learned to respect and utilize the wild floods that raged down the rivers bringing fresh nutrients to the soils, rather than diverting water sources. They used fire selectively and sparingly to clear the tangled brush lands, promote new growth, and drive prey to hunting fields. Having settled in permanent winter villages, they carefully rotated their hunting grounds and gathering fields on a regular basis in order not to deplete them. Their diets and eating practices encouraged light meals shared by an entire family and often friends. They consumed only what nature furnished and they killed and gathered only what they had need for. Waste was discouraged. Their social practices were just as important. Family moieties divided society into two ritual groups with barriers to certain unions. Strict adherence to marriage rules and the restrictions of countless family traditions, strong taboos, the important teachings of elders, and birth control all helped prevent overpopulation. Around 400 to 700 years ago, a totally different group of people settled above the Wukchumni and Yaudanchi villages. These people came from the desert areas east of the Sierra Nevada where there were fewer resources, where the Shoshonean Paiute culture practiced stream management and irrigation and had strict divisions of property. They were a more competitive people for whom warfare could guarantee survival. Known as the Monache or Western Mono, they moved into the 3,000 to 7,000 foot elevation hunting grounds of the Yokuts over a period of many years, and they, too, followed careful conservation and preservation practices.

Most of the Western Monache who settled in the Tulare Country area lived in small family groupings. The hunting camps, plant gathering bases, and trading stations that they called home lay in traditional Wukchumni and Yaudanchi hunting territories and were set up and disbanded regularly. On the Kaweah River, the merger of the two groups seems to have been a friendly one with intermarriages and joint use of hunting and foraging lands. The Wuksachi and Potwisha (Padwisha) sub-tribes of the Monache created semi-permanent settlements above the current town of Three Rivers. One major village was at Hospital Rock, where Sequoia National Park maintains an interpretive display about their known culture.

The Tule

River people had a different history from that of the Kaweah’s. The Yaudanchi Yokuts had long enjoyed at

least five permanent villages on all three forks of the Tule down to today’s

San Joaquin Valley town of Porterville. However, the Monache who migrated into

the upper Tule territories came from various

areas. Some came directly from the eastern Sierra and some drifted from

the Kaweah River, but the competitive Paiutes from the Owens Valley also had

camps in the Tule area’s highlands. Constantly moving in and out of Yokuts

territory, they evidently engaged in

small territorial battles on occasion.

Most of the prehistoric Yokuts and Western Monache sites have been lost -- destroyed by time, adaptive usage, neglect, vandalism, and treasure hunters. A few exist only as scattered rocks, grinding holes, cupules, painted and pecked drawings on large boulders, and a few uncovered artifacts. Those that are known are almost all hidden from the public, in an effort to protect them. Many of these places are still used by descendants of Tulare County's first residents. And, fortunately, there are a few sites that all of us still can visit today.

Two interesting automobile tours provide wonderful glimpses into Tulare County’s prehistoric past. One is in the drainage of the Kaweah River. The other is in the watershed of the Tule. Filled with beauty, questions, and mysteries, these tours offer many clues to what life was like for the vital people who lived here so successfully for thousands of years before written history came to our county. There is much we can learn from them for our own lives today. November, 2014 Directions:

Suggested Native American Treasures Tours: (NOTE: These Treasures are irreplaceable, often fragile, and very important to the descendants of the people who created them, so always admire and study them with care and respect.)

Kaweah River Tour Open year round to Hospital Rock; the road is usually open beyond Hospital Rock, weather permitting; carry chains in winter. Start in Visalia at the Tulare County Museum’s extensive basket and Indian artifacts display at Mooney’s Grove (free, Wednesday through Sunday, 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.). Take Highway 198 east from Visalia to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Lake Kaweah Heritage Visitor Center, where displays include a bedrock mortar that has been retrieved from a village site inundated by the lake. Continue into Three Rivers and stop at the Museum (42268 Sierra Drive/Hwy 198) to see the Native American structures outside and artifacts inside. Proceed to the entrance to Sequoia National Park (entrance fee charged) and stop at the Ash Mountain Visitor Center for information, exhibits, book store, and shopping opportunities. Stop at Hospital Rock to see the archaeological display and the original prehistoric rock art across the road. Complete your tour at the exhibits at the Giant Forest Museum or turn right onto the road to Crescent Meadow, where Kaweah River Indians led Hale Tharp in the mid-1800s to graze his cattle in the meadow beside “Tharp’s Log.” Enjoy the beautiful, easy walk from Crescent Meadow to Tharp's summer home inside this fallen sequoia at nearby Log Meadow. If you have time on your way home, stop in the parking lot across the road from Potwisha Campground in the Park foothills and follow the small trail upriver toward the suspension bridge. You'll see more Indian grinding holes, and, if you look carefully, you'll spot more rock art. As you continue west on Hwy 198, take the 2-mile detour south to Exeter to look at two large murals depicting Yokuts people. Tule River Tour

Open mid-May to mid-November, depending on weather.

Take Hwy 190 east from Porterville to Springville. Take Balch Park Dr. (J37) north from Springville to Bear Creek Road and follow Bear Creek Road to Balch Park. Go past Balch Park to a turnout on the west side of the road with a large wooden sign designating Sunset Archaeological Site. Interpretive signed trails lead to prehistoric bedrock mortars, mysterious rock basins, and Sunset Point. Alternatively, take Hwy 198 east from Visalia past Exeter to Yokohl Drive (M296) and follow it to Balch Park Dr. Follow Balch Park Drive and Balch Park Road to the Sunset Archaeological Site parking lot. An added attraction on this route is a historic marker along the road designating Battle Mountain. A loop trip using both routes is recommended. |